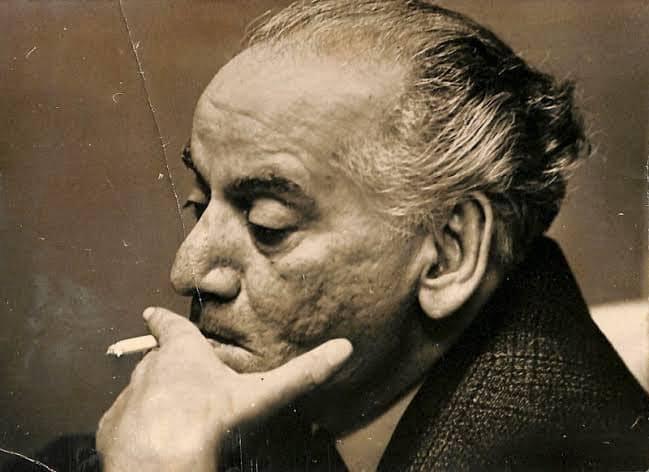

How did the language of Faiz Ahmed Faiz — the poet whose verses echo across continents, whose words have been translated into dozens of languages — become something we punish children for speaking in schools?

How did the language sung by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, whose voice brought tears to listeners from Tokyo to Toronto, become a symbol of “backwardness” in the very country it was born in?

It’s actually heartbreaking.

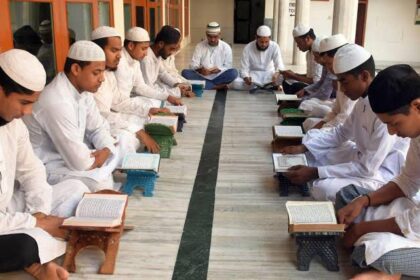

You walk into a classroom in Pakistan, and there’s a rule painted boldly on the wall: “Speak English Only.” Students are warned, scolded, and sometimes even fined for speaking in Urdu — their own mother tongue. It doesn’t matter if they were expressing themselves clearly. It doesn’t matter if they were actually making sense. If it wasn’t in English, it wasn’t “good enough”.

And that’s what our schools are teaching kids without ever saying it directly: that Urdu — the language of ghazals, of resistance, of beauty — is something to be ashamed of.

Let that sink in for a second.

No one’s saying English isn’t important. It is. We live in a globalised world — English opens doors, sure. But the problem isn’t English itself. The problem is how we’ve made Urdu seem less than. Like it’s a stain that needs to be scrubbed out of a child’s speech.

Imagine telling a kid that speaking the same language as Iqbal, as Parveen Shakir, as Ghalib, makes them sound “uncivilised”. That using the words their grandparents spoke with pride is something to be corrected.

It’s not education. It’s erasure.

Other countries don’t do this. In Japan, in Germany, and in France — students learn in their own languages first. English is taught, but it’s never used to belittle their roots. Their languages are part of their national pride.

Here? We’re too busy telling a child to “repeat that in English” instead of actually listening to what they said.

What message are we sending?

Is that to be smart? You must sound foreign.

Is it that to be successful, you must first unlearn who you are?

It’s absurd.

Urdu is more than just a language. It’s our soul, our rhythm, our identity. We quote Faiz when we grieve. We hum Nusrat when we fall in love. We dream in Urdu. We pray in it. We fight in it. We heal in it.

If we make our kids feel embarrassed about it, we’re not just hurting their confidence — we’re cutting them off from their own heritage.

Let our children speak freely. Let them speak both English and Urdu with pride. Let them carry Faiz’s fire and Shakespeare’s sharpness in the same breath.

Because a child who can express themself in any language is powerful.

But a child who can express themself in their own language — that’s something sacred.