“God made us victorious because we named our military operation Bunyan al-Marsoos after a Quranic verse. The victory of our armed forces against India is the victory of the whole Muslim world.”

These were the words of a Friday sermon I attended one week after the war.

As the dust of the recent Pak-India conflict settles, the nation has emerged with a heightened sense of what Ayesha Siddiqa refers to as a military-laced nationalism. The appeal to religious symbolism and the self-proclaimed victory over India have brought the boots—just as they were turning back to the barracks—once again into our brains. A recent Gallup survey shows that 93% of Pakistanis believe the war improved the army’s image. Yet war does not create our military romanticism; it merely reveals what has long simmered beneath the surface.

This romanticism is no accident. It is the product of decades of deliberate appropriation of religion and nationalism by military regimes to further their own agendas. In the words of Benedict Anderson, nations are imagined communities. This role of imagination in nation-building provides ample room for those in power to creatively manipulate history, education, and media to shape public consciousness.

At home, we hear nostalgic accounts of Zia’s dictatorship and his Islamisation project. At school, students read selective stories of industrial growth under Ayub Khan’s regime. Our textbooks mention the GDP growth driven by his economic policies but ignore the deepening inequalities that allowed 22 families to control most of the nation’s assets. We read about political unrest under civilian governments, portrayed as the chaos that justifies a general stepping in to ‘set things right’, failing to understand that a free political system—one which embraces diverse voices and conflicting perspectives—is meant to be tumultuous and messy. It is not supposed to be tightly controlled and hardline, like a dictatorship. Politics, ideally, is a continual process of national growth through debate, dialogue, and trial and error, not a prewritten script imposed from above.

We grew up watching Ehd-e-Wafa on television and listening to our elders recall Alpha Bravo Charlie. The military-entertainment complex in Pakistan is not just functional—it is thriving. We are obsessed with the image of the soldier as saviour: a tireless sentinel guarding our borders while we sleep. Yet we often fail to grasp that this is their constitutional duty to protect the nation’s geographical boundaries. This duty does not entitle them to intervene in civilian affairs. We celebrate military-led rescue efforts after earthquakes and floods, but we rarely ask why our civilian institutions remain so weak and ineffective in the first place.

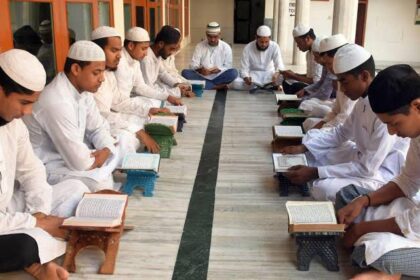

Religion has long been a malleable instrument in the hands of the military, one that can be bent to serve institutional interests. We pray for our mujahideen every Friday. Our elders were stirred by the songs of the 1965 war, infused with religious zeal. Today, those songs are reimagined by Coke Studio to rekindle the same fervour. Each year, new anthems are released to inflame nationalist sentiment. The military, media, and madrassah now form a triad where reason is drowned out by an unthinking, hyper-militarised nationalism.

Part of the problem is our discomfort with dissent. We prefer uniformity and submission over disagreement and diversity. When the military abducts political opponents and tortures them into silence, we joke about a software update. That this uncritical submission has seeped so deeply into our everyday language is alarming. The military has wrapped itself so tightly in the flags of religion and nationalism that to question it is to risk being branded a traitor—or a heretic. The soldier has not only entered our politics but every fibre of our social imagination.

The consequence is as predictable as it is dangerous: war and conflict have become tools for the army to reaffirm its role and restore its image. When the guns fall silent, people start questioning the echo of boots in our political spaces. It is, therefore, in the military’s interest to continue engaging in conflict—whether with internal dissenters or external enemies. Because in a twisted paradox, a hostile neighbour is the army’s best friend. Wars keep nationalistic spirits high and justify the continued dominance of the military. What’s at stake is not just the future of civilian leadership but also regional peace.

Peace may be boring, but the nations that have resisted the lure of military adventurism are now thriving in science, technology, and commerce. We are faced with a difficult decision: either dismantle the myth of military heroism or continue living in denial, distrusting civilian leadership and yearning for a saviour in uniform. The former requires a mental and cultural transformation: critical discourse, respect for dissent, and an honest reckoning with our history.