The thin, often indistinct boundary between dissent and deviance in Pakistan’s political landscape is a complex, emotionally charged terrain. At their core lies a joint aim to challenge authority and the state’s impulse to preserve order. When citizens protest, criticise, or organise against prevailing power structures, they claim space for democratic expression and social justice. Yet, in many instances, those same acts are reframed by authorities as deviant, criminal, or subversive.

On one hand, dissent usually refers to intentional, often vocal disagreement with policies, leaders, or institutions. On the other hand, deviants are social groups that oppose or resist the norms and values inflicted upon them by the wider society. Paul Willis analysed this phenomenon through the observation of the boys that see school as a middle-class institution that does not cater to their needs or aspirations. As a result, they feel alienated, as they do not believe that success in education will lead to better prospects for them. This belief manifests into deviant behaviours such as smoking, disrespecting their teachers, etc.

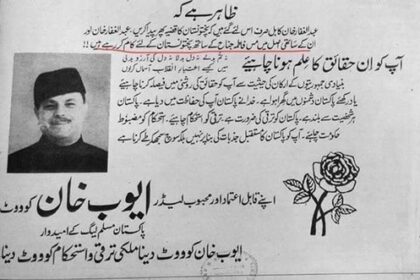

These definitions clarify vaguely what it means to ‘deviate’ or ‘dissent’ against a higher power, educational institution or the state. Although, as we recount Pakistan’s history in handling political criticism, we are able to figure out how deeply “hushed” the state pressures its population to be. Looking back to the 1950s and 1960s, Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s poems, which celebrated social justice and condemned oppression, were widely circulated despite official attempts to ban them. He was arrested under martial law in 1951 for alleged links to a communist conspiracy; his poetic dissent was recast as deviance against the state. Similar to how Bhutto founded the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) in 1967 with a platform of “democratic socialism”, conservative elites and the military establishment branded him a radical. His populist rallies in Punjab, Sindh, and Karachi drew huge crowds but were punctuated by state crackdowns and accusations that PPP supporters threatened “social harmony”. In both cases, rising political voices were exhorted to return to “national unity” (a euphemism for acquiescence) or face imprisonment, censorship, or worse. These examples illustrate how early dissent, especially when it touched upon land reform or income inequality, could be portrayed as deviance against Pakistani values.

In 1988, marked the return of civilian rule after a long-winded military rule ended, as Pakistan’s media landscape expanded. Private television channels, independent newspapers, and talk‐show culture proliferated. Yet while these outlets initially provided space for dissent, they also came under aggressive pressure whenever they crossed certain unwritten lines, especially around criticising powerful generals or discussing taboo topics (e.g., Baloch separatism, the blasphemy law). Due to the fact that Pakistan’s constitution guarantees freedom of speech and assembly, a range of laws—the Official Secrets Act, anti‐terrorism statutes, and the blasphemy law—can be wielded to silence critics. Because these laws contain vague or broad clauses, authorities can easily shift a dissenting action into the realm of deviance. As a result, journalists who reported on alleged military misconduct, such as the missing persons cases in Balochistan, faced accusations of “libelling the army”, a clear effort to reframe their dissenting reporting as deviant, anti‐state propaganda.

Even as politicians like Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif campaigned on platforms of greater accountability, their very calls to hold the military accountable were sometimes portrayed by pro-establishment outlets as emotional instability or anti-institutional sentiment. Thus, while formal political channels reopened, the underlying game of labelling certain dissenting topics as beyond the pale continued, rendering the boundary between dissent and deviance persistently fragile.

Military, intelligence agencies, religious authorities, and political elites often collaborate to decide which forms of dissent will be tolerated. When they perceive a challenge to their combined interests, they act swiftly to stigmatise participants. This stems from the collective fear of precedent, as once a protest succeeds in forcing policy change, other groups may be emboldened. Authorities, fearing a domino effect, often choose to criminalise protests early to prevent them from setting a “dangerous precedent”. The very labelling of dissent as deviance is thus a pre‐emptive move to deter future mobilisations. This can be seen following Imran Khan’s removal from office in April 2022; his party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), launched massive sit‐ins (dharna) in Islamabad and across major cities. Supporters argued that Khan’s ouster was the result of a “foreign conspiracy” and that protesting unconstitutionally elevated the masses’ voice. The government, however, labelled these demonstrations as “anti‐state” and “inspired by militants”, using anti‐terrorism laws to detain prominent PTI leaders. Media outlets close to the military repeatedly framed PTI’s sit-ins as lawless throngs blocking traffic, violating public order, and therefore deviant. In reality, the protests, while at times disorderly, were principally political expressions of grievance. The state’s recasting of mass mobilisation as deviant illustrated how quickly legitimate dissent can be criminalised when it challenges entrenched power networks.

As more citizens witness nonviolent dissenters being labelled criminals, confidence in the judiciary, police, and legislature erodes, fuelling cynicism and apathy.

By examining cases like the PTI sit-ins, we see how genuine demands for accountability and human rights are too often recast as deviant threats to the national fabric. Yet the very persistence of these movements suggests that this boundary can be redrawn: through judicial interventions, grassroots mobilisation, and principled political leadership. Recognising how easily dissent morphs into deviance is a call to resist the stifling of voices that refuse to be marginalised, to safeguard spaces where disagreement can flourish without fear.

Ultimately, Pakistan’s future hinges on whether its institutions and citizens can tolerate the unease of political disagreement. If they succeed, the line between dissent and deviance may finally become not a weapon to suppress resistance but a mutual understanding between the state and its people.