For decades, Pakistan’s film industry has been steeped in romance, family drama, and nationalist thrillers. But when it comes to horror—the genre built to make our skin crawl and make it difficult to fall asleep without flinching—it’s absent from mainstream cinema. Pakistan continues to experiment with family drama in every regard, but when it comes to horror films, it’s proven to be quite lacklustre.

So why can’t Pakistan make scary movies? The answer lies in this clustered web of industry caution, censorship, outdated perceptions of audience taste, and structural barriers. Pakistani filmmakers themselves admit the industry of horror is quite tricky to nail. In fact, writer-producer of Waar and Yalghaar, Hassan Waqas Rana, bluntly told reporters: “High-concept stories require a lot of work, and unfortunately, most of our directors and producers do not have that great an opinion of our audience… Even if the filmmakers do, they don’t actually believe in themselves enough [to pull it off].” Horror often deals with subjects like death, mental illness, sexuality, and the occult — topics that are either censored or seen as shameful. Despite the increasing knowledge and awareness about these topics, there is still a taboo around them, which restricts filmmakers’ ability to portray a chilling movie; they often worry about offending conservative audiences or religious groups.

The Central Board of Film Censors (CBFC) routinely bans or demands cuts to films that depict supernatural elements in a way that shows Pakistan negatively. With no clear guidelines, self-censorship is common. Horror depends on atmosphere, sound design, and practical or CGI effects, which are really expensive. Pakistani productions often lack the funding or expertise. Low budgets are often cited as a barrier, but horror historically thrives on limited resources. However, researchers believe the real problem isn’t money; it’s belief. Doctor Hasan Zafar, a media researcher, argues that budgets ($300K–$500K per film) could support horror—if producers weren’t so formula-bound. “It’s about priorities,” he suggests. “There’s no interest in building genre diversity.”

Despite success abroad, In Flames (2023), a horror movie about a Pakistani woman named Mariam who, after the death of her father, faces a world of male oppression and supernatural forces in a patriarchal society, was turned down by distributors. The film explores the harsh realities of women’s lives in Pakistan, particularly those who are vulnerable and lack legal protection, and struggled to find Pakistani screens. Kahn had to rent cinemas in Karachi and Lahore to show it himself. What was the issue here? A potential answer could be that our television screens are overrun with wedding comedies and Eid blockbusters. As filmmaker Asim Raza (Ho Mann Jahaan) noted, “Stories should come from society… but all we give is formula entertainment. There should be something that makes people think.”

Besides In Flames (2023), filmmaker Usman Mukhtar’s short film, Gulabo Rani (2022) was able to gain immense traction on YouTube, as there was a reluctance in Pakistan to show it on the big screen. The film tapped into Pakistan’s rich history of folklore and ghost stories and followed a young man with modest means trying to fit into a private, elite college, where he has to deal with relentless bullying by his peers, till he finds himself possessed by a spirit and seeks revenge on his tormentors. This film turned out to be a huge success; it received several awards throughout the world, including best horror short film at L.A.’s Indie X Film Festival. If the film was given importance on the big screens, the message showcased both the culture of bullying and the changing socioeconomic classes in Pakistan, and could’ve been a key way to spread awareness and allowed institutions to implement restrictions.

The younger generation in Pakistan is consuming horror from the U.S., the U.K., Korea, and even India. Young audiences are trying to get Pakistan to expand their horizons by continuously asking for psychological thrillers or horror that feels real.

“Independent filmmakers are trying”, it has been said, “But the big shots don’t want to risk anything new.” The success of international horror proves there’s a market. What’s missing is support. The future isn’t bleak. The groundwork is being laid by directors like Zarrar Kahn. Streaming platforms are opening space for experimentation. Festivals are showcasing South Asian horror because this genre can be a powerful way to explore collective trauma and suppressed stories in Pakistan. The genre’s ability to convey fear, unease, and supernatural activities allows social taboos, historical violence, and silenced narratives to be expressed in ways that are both emotionally impactful and culturally relevant.

In a Pakistani society, where open discussion of traumas is often avoided, horror provides a creative way to confront these issues. For example, ghosts or haunted spaces can represent the lingering effects of partition, sectarian conflict, or generational trauma.

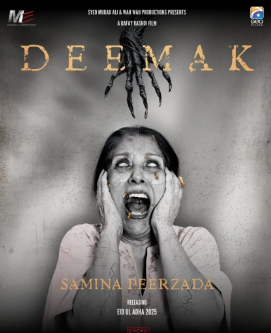

However, it isn’t completely fair to say Desi Horror is abolished from Pakistani screens; it can be assessed that the movies portrayed on the big screens are unable to be separated from the same repetitive topics, e.g., marital problems. The potential in the industry is present, but unless Pakistani producers start taking this storytelling seriously, horror will remain a ghost in the nation’s cinematic attic. It’s time we asked: in a country full of real-life fear, why are our movies so afraid to be scared?

Pakistan’s horror block isn’t due to the lack of material available; it’s due to structural and cultural barriers. But horror remains a potent genre for telling hard truths in disguise. If independent filmmakers are given more leeway and support, Pakistani horror could rise not just to scare but to confront issues which are suffered in silence and bring light to them. The potential of our filmmakers cannot be denied, but they need more support from audiences and distributors to showcase their creativity and change the narrative around this genre. If this type of support is provided, Pakistan’s film industry can spread its wings and fly, not just in the confinements of South Asia but beyond its realms to international borders.