Human nature doesn’t change; rather, it evolves from burying our daughters as a disgrace to forcing them to choke on their dreams and retiring them to early coffins. We have simply progressed. They learn to crawl through the dirt, soil caked beneath their fingernails, digging until their nail beds bleed, all for a glimpse of freedom that was never promised to them. Mature minds in stunted bodies, creases between brows—a youthful look roughened by time.

How do you mourn something that was never yours? How do you know that the primal ache in your ribs is because you were peeled away layer by layer, evicted from your childhood? Spines bent to accommodate the weight of responsibilities tethered to them, giving them no margin to be girls, to simply exist. Being carefree was a foreign concept. Girlhood was something never inherited. The only inheritance they ever received was the “how to grow up without being grown” handbook: dog-eared and dutiful.

Amongst the many luxuries our working-class daughters deem out of their grasp is their supposed girlhood. Where some have the means to indulge in expensive meals, others tend to skip them to save a few rupees. A coin is flipped every time a girl is born, lucky for her to be given to a wealthy family, while the one given to a working-class woman has her timer started since her foetus is in position in the womb. Just like clockwork, they move around, stuck in a life they could never escape.

Society imagines girls to be carefree and lively, those privileged enough to spend their years making friends, bunking lectures and planning birthdays—they are handed everything on a silver platter, whilst working-class daughters have every second indebted to them. Their only role in this life is to be of service, a second parent for children they never birthed, a chef for food they’ll never eat, and a cleaner for houses they don’t live in. Their lives are no more than a Shakespearean tragedy: stolen, wronged, and discarded. Their girlhood ripped off of their backs is then distributed as scraps for the entitlement of others. These girls are shuffled like a deck of cards, one traded in for another—job, partner, sacrifice.

Employed as maids, their feeble bodies being moulded to take on the weight of chores no normal person could execute, being treated as a rusted machine, not bothering to be oiled yet still being taken advantage of. Life at home isn’t any better; labour has been written in their destinies, whether in their own homes or someone else’s, whether it is tending to their siblings or mopping someone else’s floors. Every day, while they work in the houses of the fortunate, they come in contact with versions of themselves they could’ve been if life was just a tad bit kind to them; they too would spend days scrolling—mentally ticking off their online purchases, pouting and throwing tantrums. Instead, they dust away their aspirations and yearnings to be more.

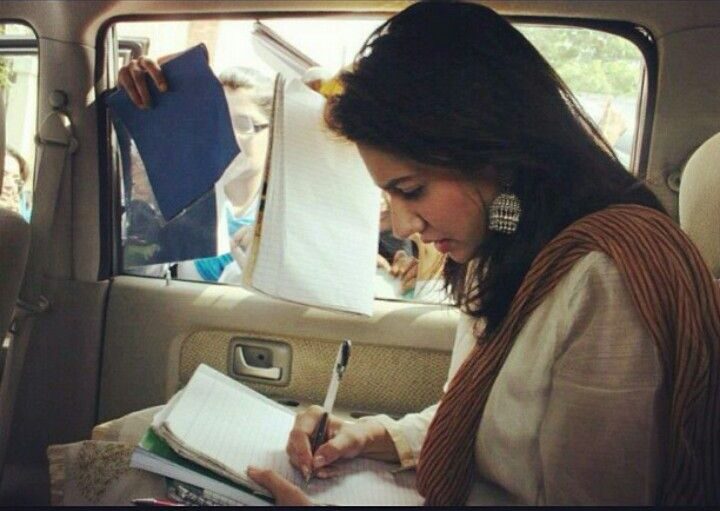

According to a 2022 report by UNICEF Pakistan, 1 in 3 girls in urban slums takes on domestic labour roles by age 12, either inside their own homes or as maids. Misery knows no bounds, certainly not for these daughters. Their circumstances take a physical toll on them, with throbbing bodies being pushed to the verge—with mental tensions into the bargain. Repeated whispers of money not being enough, barely surviving on the brink of poverty, hushed whispers turning into agonising screeches from one parent to another; the same tumultuous days being repeated over and over make it hard for even a grown-up to not spiral, yet these daughters persist, showing up to work with the utmost consistency, not indicating what happened prior. At 12 and 11, they are more mature than any one of us could ever dream of being, working their way to earn their lawful money and becoming a connoisseur in rationing each penny to suit their family.

12.5 million children in Pakistan are involved in child labour. Girls often remain invisible in this data as they work in homes, not factories. School becomes a fever dream, one they admire from afar but duck their heads away from. Education leaves a bitter taste on their tongue. They don’t have time to get dressed or trek to school—no, not when they’re better off as wives to older men deemed as supposed “caretakers”. Once again, they are robbed, cursed with the idea of dreams they come so close to but are snatched right in front of their eyes. This abominable blend of patriarchy and poverty, the impeccable need to exert control costs these girls their childhood. Their innocence is no longer theirs. It is branded as security: to be married off at 14 is considered safe. Young girlish faces get decorated with bridal makeup; they don dresses, carrying the weight of their desires underneath the veil.

UNICEF says that around 21% of girls in Pakistan are married before the age of 18; 4% before 15. By textbook definition, girlhood is showcased across our platforms as one vibrant spectrum. Arising from pastel colours, diaries, poetry, girlfriends and the creative, serene aspect of it all. But people forget this version is limited to those within a specific class; our working-class daughters experience a far different reality from them. This myth is solely based on fiction—of course, those who can afford it do, but what about those who can’t? Are they unworthy? Doesn’t every daughter deserve a chance to be a girl? Girlhood has become a hashtag now; a brand more than reality, a way to separate the elite from common people. These girls don’t have the time to revert to their teenage years, not when they act as backbones, bearing the brunt of being the breadwinner, little mother, caretaker, wife, househelp and maids.

Our elders claim that girls need to be treated as delicate flowers to bloom—a blessing of God—yet they never include those hardened by the frayed edges of their longevity, those who were never handed the privilege to be taken care of. They don’t get to cry over report cards or teenage crushes. Their tears are reserved for real loss, abandonment, hunger, and imminent burnout before even growing into a woman.

Girlhood was not a favour to be bestowed but rather their birthright, one they had been denied all their lives. Impersonators in their own homes, forcibly transformed into mature women. In Pakistan, these stories aren’t rare; they have become routine. Until one of us pulls our daughters from their graves and brushes the dirt from their clothes, this cycle may never end. Not before swallowing another girl who dared break free from her shackles, vanishing her before she’s even allowed to call herself a girl. How many more must be sacrificed for them to live?