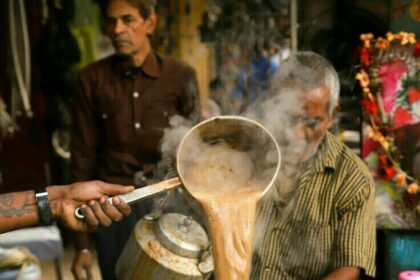

In recent years, desi fashion has made staggering aesthetic leaps: palatial bridal shoots, dreamy lawn campaigns, and Instagram feeds bursting with opulence. Designers like Elan, Sana Safinaz, and Mohsin Naveed Ranjha have mastered the art of visual spectacle. Yet amid the glossy fabric, gilded jewellery, and impossibly perfect models, one truth remains hidden. The hands that made it all possible are nowhere to be seen.

Desi fashion campaigns have a labour problem, not just in how workers are treated, but in how they are consistently erased from the visual narrative. In a culture already stratified by class and caste, the invisibility of artisans, tailors, embroiderers, and studio workers is not just a moral blind spot. It is an aesthetic choice—and a deeply political one.

Labour as Background Noise

Walk into any fashion studio in Karachi or Lahore, and you’ll see young boys threading sequins, women hunched over embroidery hoops, or master tailors bent in precise concentration. These are the real architects of couture. Yet when the final product is unveiled in a glossy ad or bridal film, their presence disappears entirely.

There is no mention of the woman who stitched the gota kinari or the karigar who hand-dyed the dupatta in seven shades. No credits, no acknowledgements, not even behind-the-scenes content. The campaigns instead spotlight models lounging in antique mansions or walking through fields, the clothes seemingly conjured from air.

The disconnect is jarring. Fashion rooted in heritage and craft revival has, ironically, erased the craftspeople themselves.

The Aesthetics of Clean Wealth

This erasure is no accident. It ties into the visual culture of elite aspiration. Desi fashion campaigns are crafted to appeal to the bourgeois desire for refinement without confrontation. They show wealth without labour and tradition without hardship. In this narrative, the labouring body is out of place. Sweat has no space in silk.

Campaigns often stage rural settings—mud houses, charpoys, and clay pots—to evoke nostalgia. But the people who actually inhabit those settings are cropped out, replaced by fair-skinned models posing as a sanitised version of authenticity. The poor are romanticised but never humanised.

This creates a double erasure. The worker is absent both in process and in portrayal.

Gendered and Caste-Based Invisibility

Most of the invisible labour in desi fashion is also gendered. Women do much of the intricate embroidery and stitching in informal setups, often from home-based sweatshops or under exploitative conditions. These women are uncredited in a system that thrives on their skill but denies them dignity.

Furthermore, in regions like Sindh, Punjab, and Rajasthan, many artisans belong to historically marginalised caste communities. Fashion’s silence on caste and the historical exploitation tied to textile work reflects its larger detachment from justice narratives. It wants the look of tradition, not the weight of responsibility.

When Activism Is Aestheticised

To be fair, there are moments when fashion nods to social justice, but often these gestures feel hollow. A model wears a thaila to make an environmental statement. A shoot in an old haveli features a child labourer in the background, presented as rawness. Sometimes, brands shoot in a brick kiln or village but fail to credit the space or acknowledge the people who live there.

This selective moralising—where activism becomes a filter rather than a framework—only reinforces the problem. Desi fashion wants to be global, ethical, and glamorous, but not accountable.

Towards Ethical Visibility

So what would ethical visibility look like in desi fashion?

It would start with crediting artisans and craftspeople. It is a small but revolutionary act to name the woman who did the embroidery or show the team behind the handwork in campaign materials. It would also mean fair wages, better working conditions, and removing the veil of secrecy around supply chains.

Brands could shift their storytelling to include process-based content, not just final shoots. Imagine a campaign that traces a bridal lehenga from concept to completion, featuring interviews with karigars, dyers, and cutters. Imagine if the glamour of the product included the dignity of the people who made it.

And yes, it would mean discomfort—acknowledging class hierarchies, the sweat behind the sparkle, and the exploitative structures built into the industry. But fashion has always had the power to challenge norms, not just mirror them.

Examples of Hope

There are glimmers of change. A few independent designers in Pakistan and India have begun to include their workers in visual campaigns, sometimes even in fashion shows. Brands like Rafugar and Sukoon Active have foregrounded slow fashion and labour ethics. In India, designers like Rahul Mishra have consistently spoken about the centrality of artisans in couture.

Still, these remain exceptions. The mainstream aesthetic economy continues to run on the quiet suffering of the many for the visual pleasure of the few.

Conclusion: What We Choose Not to See

Fashion tells stories—not just of style, but of power, privilege, and exclusion. When desi campaigns exclude labour, they tell a story of class elitism masked as culture. They promote a fantasy where clothes are handcrafted—but not by human hands.

To truly honour desi fashion’s legacy, we must begin with recognition—of the labour, the labourer, and the systems that make beauty possible. Until then, every lehenga worn, every shoot shared, carries with it a ghost: of someone whose work is seen but whose name is forgotten.