Pakistan: Remembering What the State Forgets

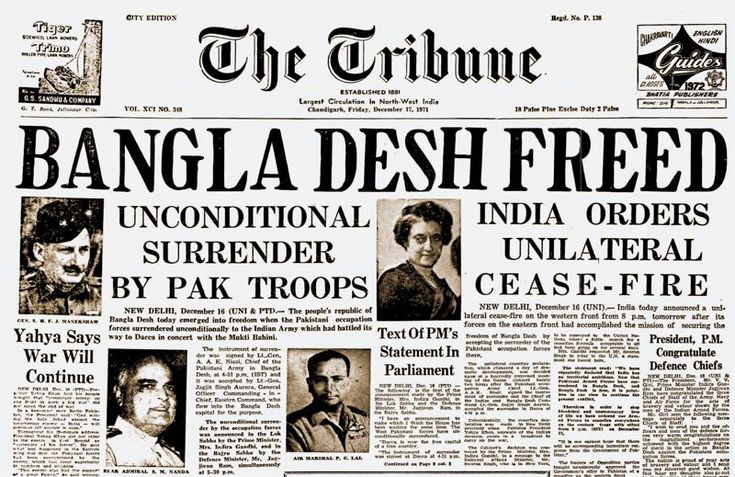

In Pakistan, fiction has long served as a counter-memory to the state’s often manipulated historical narratives. The 1971 war with Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) is a particularly glaring case. For decades, the atrocities committed by the Pakistani military during the conflict have been largely omitted or whitewashed in official histories.

Sorayya Khan’s novel Noor (2003) confronts this silencing. The story revolves around a Pakistani-American woman and her adoptive daughter, Noor, a war survivor. Through Noor’s memories—fragmented, painful, and partial—Khan reconstructs a deeply uncomfortable history of rape, violence, and abandonment. The novel refuses resolution. It archives not by presenting an objective truth, but by offering a landscape of suffering that the Pakistani state has tried to erase.

Similarly, Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007) is not just about 9/11; it’s about how Pakistani identity is always in negotiation with state power and Western surveillance. Through its metafictional narrative, the novel acts as both testimony and mirror to a state that demands silence on certain political matters—be it the army’s role in Balochistan, sectarian killings, or the forced disappearances in Sindh.

These novels speak into the void left by censored journalism and textbook euphemisms. They are fictional, but their truths resonate because they say what cannot be said elsewhere.

Palestine: Fiction as Witness to Dispossession

Nowhere is fiction’s role as a witness more urgent than in Palestine. Denied statehood, fragmented by occupation, and subjected to a systematic erasure of memory and narrative, Palestinian literature functions as archive and resistance.

Ghassan Kanafani, perhaps the most iconic literary martyr of Palestine, transformed fiction into a powerful tool of memory. His novella Men in the Sun (1962) recounts the death of three Palestinian refugees who suffocate in a water tank while being smuggled to Kuwait. The metaphor is devastating: the silence of their deaths mirrors the world’s indifference. Kanafani was assassinated by Mossad in 1972—his death a grim confirmation of the potency of Palestinian narrative.

More recently, Susan Abulhawa’s Mornings in Jenin (2010) performs the function of an intergenerational archive. Following a Palestinian family displaced in 1948, the novel meticulously documents key historical events: the Nakba, the refugee camps, the Lebanese civil war, and the Intifadas. This is a people’s history, one that refuses to erase names, homes, and traumas.

Palestinian fiction is not simply storytelling; it is an act of reclamation. Where maps have been redrawn and histories denied, these novels keep memory alive—not as nostalgia but as a political act.

Chile: Fiction as Post-Dictatorial Reckoning

In post-dictatorship Chile, fiction became a crucial medium for unpacking the brutal legacy of Augusto Pinochet’s regime (1973–1990). With thousands tortured, killed, or “disappeared,” and with state-sanctioned denials still circulating, literature has shouldered the responsibility of historical reckoning.

Roberto Bolaño’s By Night in Chile (2000) is an exemple of this literary confrontation. The novella, narrated by a dying priest who once aided the regime, is a fevered confession full of omissions and half-truths. Bolaño dissects the complicity of Chile’s elite—particularly the clergy and literary class—with the fascist regime. The narrative, elliptical and darkly poetic, becomes a map of moral failure and silence.

Likewise, Diamela Eltit’s E. Luminata (1983), written under strict censorship, uses fragmented prose and experimental structure to critique surveillance, patriarchy, and authoritarianism. Eltit’s work, while not linear or “realistic,” functions as a code—a resistance manual against the symbolic violence of the state.

In Chilean literature, the act of writing becomes an excavation of memory buried by terror. Fiction does not merely recall history—it enacts its refusal to disappear.

Kashmir: Writing Against Occupation and Forgetting

In Indian-administered Kashmir, where decades of military presence, insurgency, and mass human rights violations have turned the region into a war zone, fiction operates in an atmosphere of intense surveillance and suppression. Here, to remember is to resist.

Mirza Waheed’s The Collaborator (2011) is a haunting tale of a young Kashmiri boy working with the Indian Army to identify bodies of militants. His task is macabre—counting the dead, many of whom are his friends. Waheed’s novel is an indictment of occupation and also a meditation on complicity and silence. The landscape is brutal, but so too is the psychic violence of enforced forgetting.

Similarly, Shahnaz Bashir’s The Half Mother (2014) centers on Haleema, a woman whose son is taken by Indian forces and never returned. Bashir writes from within the trauma of enforced disappearances, a phenomenon that official narratives either deny or downplay. The novel becomes an unofficial archive of grief, insistently asking: Where are the bodies? Where is justice?

Kashmiri fiction today acts as a ledger of trauma. These novels are populated not by heroes, but by mourners—people burdened by memory in a land where remembering is almost seditious.

Conclusion: Fiction’s Dangerous Power

This brings us to a final provocation: Can fiction be trusted as history when the state cannot? Or does fiction merely offer a more palatable lie, one that consoles rather than confronts?

The answer may lie in recognising fiction’s dual role—as both insurgent and compromised, as both liberator and mythologizer. It is not pure, nor should it be. But its impurity—the messiness of emotion, the unreliability of memory, the ambiguity of metaphor—may be the very qualities that make it more accurate than “official” history.

Fiction’s strength lies not in its empirical accuracy but in its capacity to restore moral clarity, to narrate the affective truth of collective experiences. When censorship turns journalists into martyrs and teachers into propagandists, it is the novelist who often assumes the dangerous task of national remembering.

To read such fiction is to confront what official histories will not show. It is, in the words of Edward Said, “to reclaim the land of memory for those who have been denied a place in the narrative.”