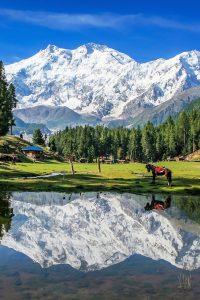

Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), a region of unparalleled natural beauty and immense geopolitical importance, sits at the crossroads of history and neglect. Officially described as an autonomous and self-governing region of Pakistan, the area is in political oblivion. For over seven decades, GB has been caught in a web of constitutional ambiguity, political exclusion, and unfulfilled promises. Despite its pivotal role in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the region remains marginalized and deprived of basic political and representative rights.

On November 1, 1947, GB scouts liberated the region from Dogra rule, establishing a revolutionary interim government under Shah Rais khan as the governor. However, this independence was short-lived, lasting just 16 days before the region joined Pakistan without a referendum. This controversial accession marked the beginning of an era of political and constitutional neglect. It has been almost 77 years since and Pakistan has been unable to integrate the region constitutionally, while it has constantly been using GB’s resources to its benefit. Despite its extraordinary importance to the country’s economy, GB has been subjected to political exclusion and denied meaningful representation in the country’s parliament.

After accession to Pakistan, GB was placed under the Frontier Crime regulations (FCR), a draconian colonial-era law. Under the FCR people had no right to appeal, were denied legal representation and the opportunity to present evidence in their defense. Many National groups such as Gilgit league, Tanzeem-e- Millat and GB Jamhoori Mahaz opposed FCR but were brutally suppressed for demanding their democratic rights.

In 1974, Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto abolished the FCR and introduced judicial and administrative reforms. However, these efforts were derailed by the imposition of martial law in 1977. It was not until October 1994 that for the first time, party-based elections were held in Gilgit Baltistan. Although they lacked meaningful authority- an issue that persists- the upholding of these elections were a sign of the improved status of GB in state politics.

In 2009, under the Gilgit-Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order, a legislative assembly of 33 members and a GB council of 15 members was established, headed by the prime minister of Pakistan. However, very limited power was vested in the GB assembly. Most of the decisions are still made by the politicians in Islamabad. Even the region’s budget is finalized by the federal government before being sent to the GB Assembly for presentation. In the same way, the GB Council has a virtual authority that does not have any representation in the federal government of Pakistan. This exclusion has fueled widespread resentment, with locals rallying behind the slogan “no taxation without representation.” Until the people of Gilgit-Baltistan are granted representation in Pakistan’s Senate and National Assembly, Islamabad’s imposition of taxes will remain an unresolved issue.

Since elections in Pakistan and GB are held at different times, it creates the impression that the ruling party in Islamabad influences the results in GB. This fuels mistrust, aggression and resentment in people against the capital.The lack of representation in the parliament gives third parties a chance to exploit the situation, further worsening the matters.

It is worth mentioning that five seats are reserved for Gilgit Baltistan and Kashmir in the Lok Sabha (lower house) and one in the Rajya Sabha (upper house) of India. This raises an important question: if India can provide parliamentary representation to disputed regions, why does Pakistan fail to do the same? The absence of representation in Pakistan’s parliament has eroded trust in government institutions and authorities.

Gilgit Baltistan faces severe challenges in health and education. The area has poor health and educational systems with no law, medical, and engineering colleges. More than two million people inhibit the region with a literacy rate higher than other regions of Pakistan.The region’s two main universities, Baltistan University and Karakoram International University, suffer from inadequate infrastructure and insufficient research facilities. In the health sector most of the contributions are from Aga Khan Health Service and the government’s investment remains negligible.

Gilgit Baltistan’s economic and geo-political importance cannot be overstated. The region’s mineral resources and rising tourism

industry attract state attention. To address the grievances of Gilgit Baltistan, the state of Pakistan must take the government of Gilgit Baltistan in confidence. The solution to local problems can only be provided by local representatives.

Gilgit-Baltistan remains a region of unfulfilled promises. Its people are trapped between the hope of inclusion and the despair of continued neglect.The integration of GB representatives into the parliament is not only an obligation of the state, but also an opportunity to encourage inclusivity and unity within its regions. The government should reconsider the ill-timed election in Gilgit Baltistan, to ensure transparency and to build people’s trust in the system. The only way for Pakistan to progress is if it owns the regions that make it a country.

outstanding work ❤️