Imagine getting into a verbal profanity competition when you were 15. It is probably true that sometimes you thought of the most insane and utterly profane insults for the other person but ended the argument saying, “Don’t force me to speak up,” as you had this powerful feeling that you had reached an edge, and if you said anything further, it would cross the limit of acceptability.

Every word that we utter from our mouths and every statement that we make is rooted in our social setting. Everything we do is an act of political statement. The food that we eat, whether we buy it from McDonald’s or the Quetta Cafe, the coffee that we drink, the clothes that we wear, the jokes that we make, our personal choices, the words we speak—everything says something about what we believe in or what we find acceptable. Whether we are conscious about it or not, there is a specific zone of acceptability that we consider before choosing anything.

We look at the world through a socially constructed boundary that facilitates public discourse, and we try to fit our worldview to a specific window, called the Overton Window. It was developed as a proper theory by Joseph Lehman after Overton’s death.

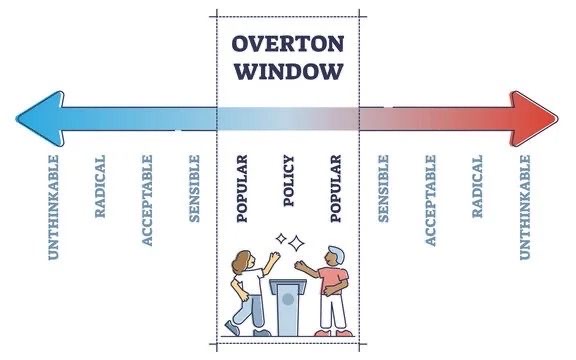

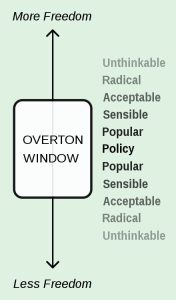

The Overton Window is the range of publicly acceptable political opinions and policy options at a given time in a society.

The Overton Window often represents the interests of the ruling class of a society. Like regular windows, this window does not exist by default; it is socially constructed, reconstructed, pushed, and pulled. In a capitalist society, media billionaires own the content that the people consume. Similarly, the curriculum, and the policies that are acceptable, are all dictated by the powerful segments of society, which include rich politicians, feudal oligarchs, and billionaires. Theykeep pushing for changes in the political structure and the window of acceptable ideas in order to move towards what serves them the best. This is one of the reasons why all capitalist societies keep regressing towards fascism.

The real fun begins when people try to move the window. Activists, comedians, artists, and even trolls play a role in this. By saying or doing things that are “outside the window,” they stretch the boundaries of what’s acceptable. Sometimes, this works, for example, when taboo topics like mental health become mainstream discussions. Another example, in the Pakistani context, can be the criticism of a certain institution of the country. The acceptability of that has been something that keeps going back and forth. The recent episode started post-2008, when, despite the successful execution of very successful democratic movements in the Musharraf era, the acceptability of criticism targeting the establishment went out of the window following the restoration of democracy. However, after 2016, it shifted again, and presently, it is quite acceptable in the society to criticise the institutions of the Pakistani establishment, though in more cryptic forms.

While it might feel like this invisible window is controlling us, the truth is that we’re part of the mob shifting it, whether we realise it or not. So, the next time you hear a politician make a wild claim or watch a movie that makes you go, “Wait, they actually made this?” know that they’re testing the boundaries of the Overton Window. And every time you tell your own stories, crack a joke, or share your opinion, you’re doing the same.

If you are a kid who grew up in the early 2000s, you probably remember going to small tech stores with names like “Dubai Computers” and “Al Jannat Mobiles” to buy a pirated CD of Windows XP. See, Windows XP is not really a window; it is an operating system. In the end, the Overton Window is just like those “Dubai Computers” shop windows we loved as kids: a little messy, full of surprises, and always changing what’s on display.