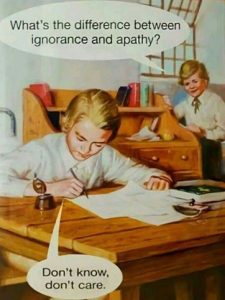

There is a callousness with which we engage with discourse today. The responsibility of making a claim and the research required for it are lacking in modern-day society, which operates on a higher digital rate than an analogue one. What’s your Instagram daily average? Peers around me easily exceed the 6-hour mark, if not 8, excluding WhatsApp and other day-to-day apps present on your phone.

With a digital life comes comforts that analogue life cannot give: a barrier between your physical, tangible existence and the abstract identity you formulate on these apps. How do you sell yourself? A barrier, however, also means lesser accountability.

Before we continue on that line of thinking, let’s engage with this:

In the introduction of The Death of Expertise by Tom Nichols, the author tells us about how discourse began to go awry—through the medical field. A California professor, by the name of Peter Duesberg, argued that Immune Deficiency Syndrome was, in fact, not caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Nichols said that science thrives on such radical discourse, but for it to actually hold weight, the premise of both extremes being discussed needs to have grounded knowledge. In this case, Duesberg made the claim with no foundational knowledge in the subject, and research later disproved him easily.

If science existed in a vacuum, this could be treated as a one-time problem—a fluke due to a baseless lunatic. However, it did not. Once Thabo Mbeki, the then president of South Africa, heard of Duesberg’s baseless claim, he chose to believe it as fact with no further verification. By denying that the cause of this disease was a virus, this man refused medical aid, and this scientific discourse, which began with one side having no expertise, caused the death of 300,000+ lives.

You see why my introduction was necessary? Claims made today don’t stay the topic of ego-infused discussions that happen on your stories and in the comment sections of controversial posts. Most discourse we engage in comes with no knowledge or theory of the terms being discussed.

Humankind evolved from linear lines of thinking long ago, once it was clear that verbal and written modes were not the only cultures of communication that existed. With the technology that we have today, verbal, written, and video tech work non-linearly, much like our processing capabilities.

A claim made in one place, with no real weight to it, travels fast, and in the wrong hands, it affects our most vulnerable populations. As a society, we have forgotten the depth of what it means to believe in something, to speak it, and to defend it. It is merely a social matter that begins and ends with hearsay. In the whirlwind of digital life, our analogue lives have become a hypocritical space that’s reactive and ignorant.

Take, for example, the mob that got together in that odd bazaar in Lahore, where a woman’s life became endangered simply due to having Arabic script on her clothes—script that had no religious beginnings. We must realize, as a society, that there are more consequences to our ignorance, and that ignorance in action easily becomes a form of oppression.

Sentiment alone is not enough to formulate our beliefs, and those beliefs have consequences, whether large-scale or small. It’s more than just an opinion, and discourse today has forgotten that when most of our issues are related to life and how it suffers, more than hearsay is needed to tackle it.

Our situation is eloquently put by Nichols in his book:

“This is more than a natural skepticism toward experts. I fear we are witnessing the death of the ideal of expertise itself, a Google-fueled, Wikipedia-based, blog-sodden collapse of any division between professionals and laypeople, students and teachers, knowers and wonderers—in other words, between those of any achievement in an area and those with none at all.”

It has become crucial to become literate, whether about the media we consume, the things we believe about ourselves and others, or the ideologies we choose to adopt. The Death of Expertise is a great book to start learning more about this problem and how to deal with it.