“The oldest and strongest emotion of man is fear.”

– Howard Phillips Lovecraft

Aristotelian Mimesis

Centuries ago, Aristotle, much like Plato before him, posited that the purpose of a play or any work of art was mimesis—the imitation of nature in structured format in search of deeper truths. In his Poetics, Aristotle argues that tragedy was a “superior” form of art, one wherein the audience could, through pity and empathy, emotionally purify themselves.

Here, one makes the case that the same could be said of fear.

One of the oldest emotions found in life on earth has been fear, a gift and a curse that has been inherited by mankind.

Fear is what kept us alive when we roamed the savannahs and jungles of prehistoric earth.

One wonders what happens then when man built for himself great cities and slowly extricated himself from the privations of a hunter-gatherer existence. What became of our fears when they had little physical source anymore?

Apotheosis

From the earliest works of fiction that we possess today can be extracted beings of wanton malice, the first daemons that haunted our collective imaginations. From Humbaba in the Epic of Gilgamesh

to Surtr

in the Norse Pantheon, man’s fears went from predatory animals and the xenophobic to inventing in our myths and fiction beings that represented the calamities and ends we collectively beheld in our phantasms. Already, one can begin to see that as soon as these fears were made manifest in beings of great power and imbued with agency in our collective psyche, they were on their way to becoming more than just fireside stories to scare the unruly youth into acquiescence.

Throughout history, our works of art and the depiction of our fears (and by extension, catharsis thereby) have inextricably reflected the human condition at the time. Whose single greatest feature, and one confesses to Schopenhaurian inclinations, is our suffering.

For the purpose of this piece, one endeavors to demonstrate the above assertion through the works of two artists, whom one has christened among the Titans of Terror: Hieronymous Bosch and Zdzisław Beksiński.

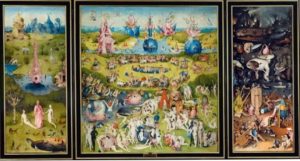

Hieronymous Bosch

Little is known about the life of Bosch; critics and scholars still dispute how many works of art must be attributed to his hand. Numerous studies of his life and work have birthed various interpretations of his art: self-flagellation, worship, didactic preaching, or the result of hallucinations. One may pick their poison.

What is known about him, however, is that he lived in the mid-14th century, and Christendom of the time was developing more and more sophisticated ideas of hell, evil, and suffering. What is also true of his epoch is the deep religious anxiety that gripped most of Europe.

It was a time when daemons and fell creatures were thought by many to be living alongside humanity, torturing and tempting the righteous into sin. A fear that would culminate in the first European witch hunts.

This interplay of fear and devotion pervades throughout Bosch’s works, and his paintings are rife with depictions of the saintly, right alongside the daemonic.

His most famous work, The Garden of Earthly Delights, is one that could warrant its own, much more detailed writing, but it perfectly depicts the nightmares the artist struggled with.

A panel depicting humanity’s journey from Eden to Hell, through Creation, the presence of strange, unsettling figures throughout the work, at a level of detail that befuddles the mind, makes this one of the greatest pieces of surrealist art.

And yet, even in less biblical paintings, the tormentors of Bosch’s imagination are not too far away.

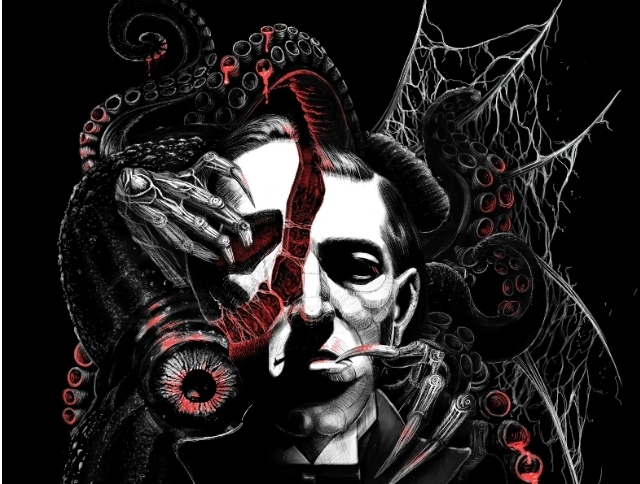

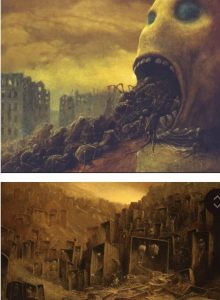

The Nightmare Artist: Zdzisław Beksiński

Born in Sanok, Poland, at just the right time to be of reasonable mental faculty by the time the Second World War tore through his country, Beksiński saw the horrors of the Holocaust and the devastation of war unfold before his very eyes. Making his debut into the artistic world with contrarian photographs, it was clear that Beksiński would become one of the great surrealists of his era.

The war devastated his homeland, exposing him to scenes of destruction, suffering, and death—imagery that later found its way into his dystopian and surreal artwork.

One of his most striking works, featuring skeletal figures shrouded in decayed robes, reflects a world ravaged by death, reminiscent of wartime devastation.

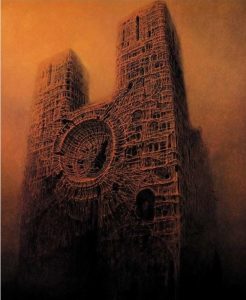

His ruined cityscapes, bathed in ominous red and orange hues, echo the burning towns and bombed-out landscapes he witnessed as a child.

The twisted, cathedral-like structures in his paintings might symbolize the fractured spirituality and despair felt by those who survived the war, only to find themselves coping with the anxiety of an apocalyptic third under a brutal communist regime.

Beksiński never provided clear explanations for his art, but his eerie, post-apocalyptic visions suggest an unconscious attempt to process the trauma of war. Though devoid of direct war imagery, his works convey an overwhelming sense of loss, decay, and the fragility of human existence. By channeling his dark memories into surrealist masterpieces, Beksiński created a body of work that continues to evoke profound introspection and unease.

The Shadows That Shape Us

Humanity needs fear. There is a reason why every gathering of cousins eventually reaches discussions of the horrifying and supernatural. From dark, primal corners of our shared imaginations, there calls upon us a gnawing desire to make the unpalatable palatable. The catharsis Aristotle spoke of in tragedy may at the end also apply to fear.

One would close by quoting another Titan of Terror, as one opened with a quote from one;

“I realized at that moment that there are some whose dread of human beings is so morbid they yearn to see monsters of ever more horrible shapes.”

– Junji Ito