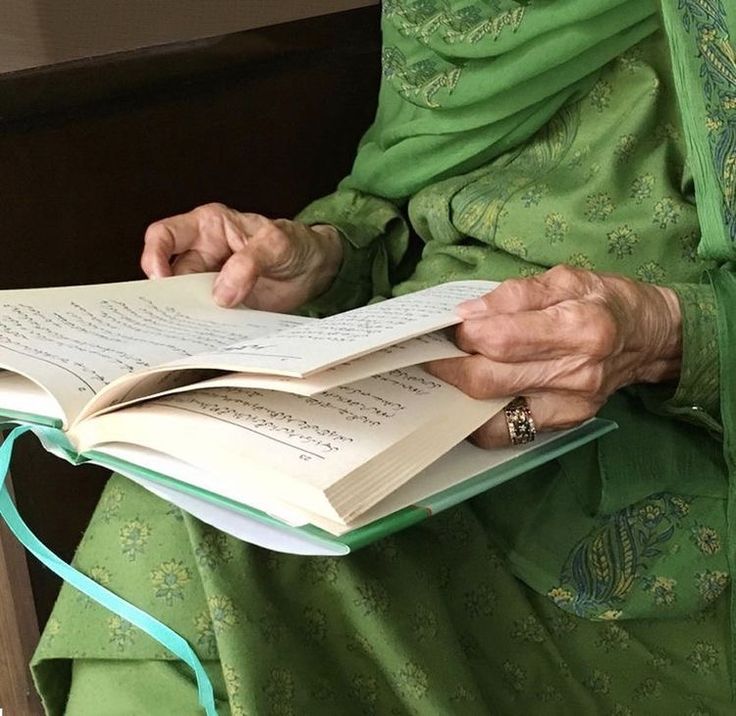

The aroma of cardamom permeates many South Asian literary works written for Western readers. The streets were flooded with monsoons like clockwork, and golden, honeyed, and symbolic mangoes blossomed from every page. The literary image of an entire region has been reduced to a beautiful pastiche by a common language of “spice”, “heat”, “henna”, and “dusty bazaars”.

This is not to say that mangoes, bazaars, and biryani are not authentic aspects of South Asian culture; they are. Rich, chaotic, sensual, and always wistful, they run the risk of becoming synonymous with an imagined elsewhere, though, when they fall into the hands of an exoticising literary tradition. What is beyond these stereotypes is examined in this article. Without promoting them, how can we write about cities like Dhaka, Karachi, Kolkata, and Lahore? What does it mean to write about South Asia as a subject instead of a spectacle?

The Legacy of Exoticism

Colonial representation is the source of this aesthetic flatness. The West viewed the East as sensual, primordial, and eternal, an object of curiosity rather than a place for subjectivity and political action, as Edward Said’s well-known essay Orientalism (1978) demonstrated. Throughout the literature, these ideas have remained consistent. Despite efforts to diversify, “authenticity” that satisfies exotic expectations is still preferred in Western publishing markets.

Apart from their literary value, writers such as Jhumpa Lahiri (Interpreter of Maladies, 1999) and Arundhati Roy (The God of Small Things, 1997) were renowned for their ability to depict South Asia in a rich, poetic manner that appealed to readers worldwide. The description of “banana flowers” and “pepper vines”, which opens Roy’s novel, creates a distinct and sensually odd sensory experience. Lahiri’s work is commended for its restraint, yet it nevertheless makes use of Indian culture as a point of differentiation that the Western reader needs to understand.

Since many of the authors are outspoken critics of Western imperialism and understand the value of representation, this is not intended as a criticism of them. Instead, it is a critique of the system that is used to sell and consume their work, which often favours readable narratives of trauma, displacement, or culinary nostalgia.

The Politics of Palatability

In the publishing industry, gatekeepers frequently demand legibility through familiarity. In South Asian literature, this familiarity is often associated with food, family, and folklore. Deepika Bahri notes in Native Intelligence: Aesthetics, Politics, and Postcolonial Literature (2003) that “ethnic difference becomes aestheticised, performing cultural distinctiveness while soothing Western liberal guilt.” Literature becomes a means of both confession and affirmation.

This is particularly true for stories from the diaspora. Though the attempt to figuratively portray one’s culture for a non-South Asian audience might weaken the narrative, the conflict between assimilation and cultural heritage makes for interesting stories. Dupattas, spices, and superstition all function as artistic backgrounds and cultural symbols.

Gaiutra Bahadur deftly examines this relationship in Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture (2013). She avoids the ornamental when writing about Indo-Caribbean indenture, instead using familial quiet and archival research to create a narrative that is neither picturesque nor simple to follow. By drawing attention to issues like violence, caste, class, and state repression that are less desirable at the multicultural buffet, authors like Meena Kandasamy and Fatima Bhutto have also questioned this conventional wisdom.

Writing Beyond the Market

How, then, can authors from South Asia and its diaspora avoid these cliches and still be read and published? Destabilising sensory detail, not allowing the mango to signify more than it should, and allowing the rain to soak a romantic city may be the answer rather than ignoring it.

Take Half Gods (2018) by Akil Kumarasamy, which uses fragmented, genre-bending writing to examine Tamil identity. The book addresses displacement and trauma directly. For example, Mohammed Hanif’s (2008) A Case of Exploding Mangoes subverts the mango cliché by wrapping it in political satire rather than love. These works resist cultural summarisation and neat closure, challenging language.

Writing about urban issues is an additional choice. South Asian cities resist romanticisation; it is difficult to categorise their turmoil, injustice, beauty, and violent past. The city is described as a living organism of paradoxes in Laurent Gayer’s 2013 book Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the Metropolis. Fiction could accomplish the same goal. Cities ought to be more than merely “settings”; they ought to be political spaces for labour, protest, violence, and survival.

Toward a New Vocabulary

Nowadays, writing about South Asia involves striking a balance between public demands and the truth. Writers need to think about their audience. And why? Writing about a place from within, speaking obliquely, diagonally, or personally, as opposed to looking up at a gatekeeper, is the most urgent.

Although not as consumable as icons, the mango, the monsoon, the biryani, and the bazaar still hold a place. Let them stay what they are: simply elements of life, neither poetic nor political unless the context makes them so. South Asian writing’s future depends on releasing sensory experiences from spectacle rather than dismissing them. If we let cities speak, they will.