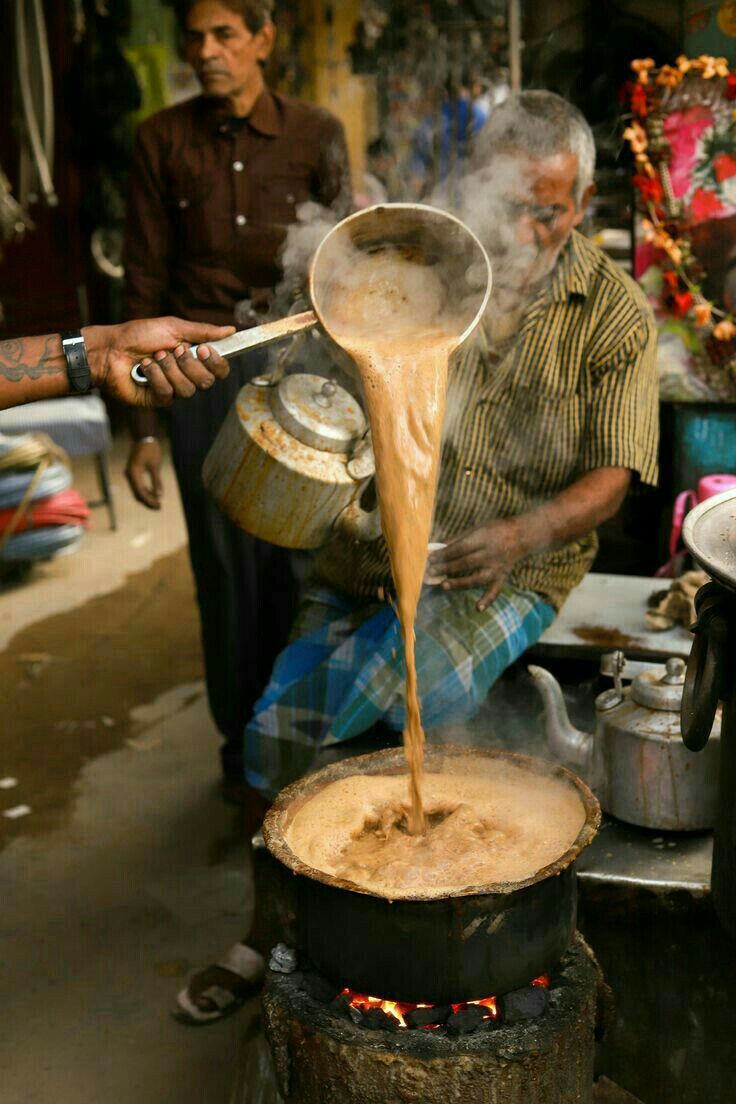

Ah! Dhaba! The “hidden gem” of metropolitan elites. A rustic fantasy where rickety wooden benches meet Snapchat filters and “chai hits different” and parathas are served with a side of theatrical humility. There’s something so real about peeling paint, sticky tabletops, and sweating through your fancy designer dress in 40°C weather simply to declare you’ve “blended with the locals.”

‘ضرورت کے مسافر، محبت کے دعوے’

Dhabas in South Punjab are more than just roadside meals; they are cultural relics that have served generations of truck drivers, labourers, and visitors. These simple rooms have recently gained popularity among the metropolitan middle and upper classes. Libra’s Laari Adda, located next to the Shell fuel station on the National Highway in Bahawalpur near Ashraf Sugar Mills, has become a popular destination for well-dressed travellers looking to experience “authentic” local culture. With smartphones in hand, these tourists are lured less by necessity than by visual attraction.

This raises a few critical questions: Who controls the narrative of Dhaba culture in South Punjab? Is it the labourers who work long hours or the metropolitan visitors who enjoy this culture as a fashionable experience?

The majority of Dhaba personnel in South Punjab come from economically challenged families, frequently relocating from smaller villages or rural areas, such as Rajanpur or the Cholistan Desert. Their workdays often last 14 hours or more, with pay that barely covers basic living expenses. Asad, a young server at Laari Adda, explained that while guests love the atmosphere, few ask about the staff’s well-being.

“The heat is oppressive, and the money is minimal. We don’t get regular days off or health benefits,” he says.

The dramatic contrast between the idealised image of the Dhaba and the realities of its laborers’ lives exposes a worrisome mismatch. While buyers appreciate the “vibe,” labourers have insecure jobs and few safeguards.

Class Voyeurism:

The practice of affluent urbanites patronising dhabas, such as Libra’s Laari Adda, exhibits class voyeurism, which involves consuming working-class culture for entertainment. Young professionals attend these venues to get a “desi vibe,” and they share their experiences on Instagram and TikTok, which boosts their popularity. They sip chai as confession, perched on the plastic tables that are now raw and chipped, resembling the bones of the working class. Then, they gaze. Not in a brutal way. Not polite. Like tourists, they gaze at a shrine of ruin. It’s so easy to romanticise the flies circling yesterday’s curry, the heat-warped glass, and the brown, barefoot child, Asad, offering sugar with ever-soft hands. It’s known as “desi aesthetics,” straight out of a Pinterest board. However, this isn’t artistic. For a thousand men who die before turning fifty, it is the pain of their dreams. Diesel breath, smoke, and oil under fingernails are all present. That isn’t a social media trend. This is class tourism, where visitors seek the poetry of the impoverished but not the politics. They want to be hungry without feeling empty. They want the perspiration without the odour.

Who Benefits?

The Dhaba becomes a stage, and the voyeurs drink up the pain like wine. They fail to see the labour architecture. They overlook the chaiwala’s secret calculation when he subtracts a meal to save a rupee. They perceive allure. While dhabas like Laari Adda gain prominence, consumers and labourers seldom reap economic rewards. Most revenues are distributed to owners and investors, local merchants, or entrepreneurs. At the same time, chefs, waitresses, and cleaners receive the bare minimum. Some franchise-style cafes demand a premium for “authentic” Dhaba ambiance but do not improve working conditions for the original employees. Influencers who promote these Dhabas online receive sponsorships, but few financial advantages reach the workers who make the experience possible. This deepens the gap between rich customers and working-class labour, hence exacerbating economic and social disparities.

Moving Beyond Aesthetics:

Dhaba cuisine in South Punjab boasts a rich cultural and culinary legacy, featuring a diverse range of dishes—from spicy channa and parathas to sweet doodh patti and samosas. But genuine respect demands going beneath the surface. Supporting Dhaba culture entails advocating for fair wages, appropriate working conditions, and worker dignity. It involves treating Dhaba workers as stakeholders rather than as background characters. To prevent labour tiredness, a few Dhaba proprietors voluntarily increased compensation or implemented rotating shifts. To elevate Dhaba culture, urban consumers and influencers must utilise their platforms to emphasise workers’ stories and advocate for equality, rather than merely the look of “rustic authenticity.”

As the flame tells the moth, what you eat for play cannot be elevated.

You cannot fetishise something you refuse to finance.

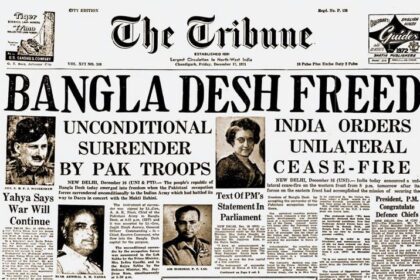

In South Punjab, Dhaba culture is no longer limited to truck drivers and farmers.

Romanticising it without addressing worker reality is a kind of exploitation disguised as respect.

Suppose we genuinely want to honour Dhaba culture. In that case, we must consider how we can support the people who bring these flavours and atmospheres to life. How can we go from consumption to solidarity?

The next time you visit a Dhaba or a cafe, take a moment to take that ideal photograph. Consider the effort, dignity, and conflicts that occur behind the scenes. Support Dhaba workers by tipping fairly, sharing their experiences, and advocating for improved working conditions.

Because genuine appreciation for Dhaba tradition is appreciating individuals, not just the ambiance. The Dhaba is not in need of your presence. It needs protection. It requires dignity rather than concealment. It’s time to quit sipping tea like it’s a poem you authored when you’re the footnote.

Absolute masterpiece. To have an eye for such an issue is rare and then to pen it down in such a way; I’m in awe.