Traitors’ trade stems from the vast capital of political economy, which is run by a certain political climate characterised by sets of political behaviours. These include hate politics, politics of othering, polarisation, political paranoia, suppression of dissent, pseudo-nationalism, and xenophobic activism. These behaviours, although always questionable on rational grounds, constitute a large part of political goods in our current political stratum.

This triggers political wrath and can escalate to war hysteria, as seen in recent Pakistan-India tensions where the major weapon of destruction was radical politics on both sides. Early assessments of these escalations also reveal a kind of political paranoia, especially across the border, which fuelled the madness and was agitated by Indian popular politics under the supervision of media houses.

In the context of Pakistan, this is exactly how the political market operates. Why the system manufactures traitors, who may then turn into heroes depending on mutual interest, is no longer a secret. The politics of enmity is a long-lasting characteristic of the Pakistani state, used both internally and externally for desired outcomes. Externally, India is employed as an ever-present political resource, a constant threat upon which the state establishes its military posture. Similarly, there is a long history of traitor manufacturing within this system. A traitor (Ghaddar) is a tool of power and a political weapon used to silence dissent and neutralise opponents. There is a long list of this political commodity being deployed by the Pakistani state, from its embryonic days and continuing with full potential today.

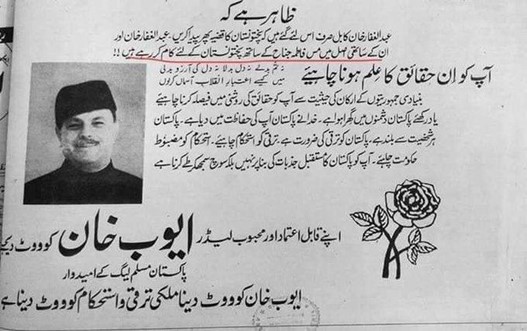

Consider Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, who was first deprived of national assembly membership and then declared a traitor. Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan), also known as Frontier Gandhi, was labelled similarly. The branding of G.M. Syed as a traitor and the trials of Faiz and Habib Jalib are part of history. Fatima Jinnah was accused of being a traitor and an Indian agent during her presidential campaign against Ayub Khan—a case widely studied. What was done to Mujibur Rahman, how Zulfikar Bhutto was hanged, the repeated allegations against Benazir Bhutto, the calls for treason against Zardari after the Memogate case, Nawaz Sharif’s treason cases over his London speeches, and recent sedition and terrorism cases against Imran Khan all show that instead of accountability or legal penalties, the culture of labelling someone a traitor has consistently been a source of political mitigation.

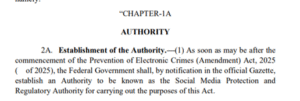

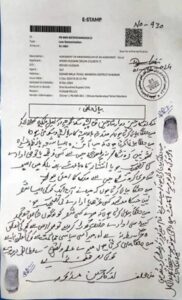

Treason cases or extrajudicial penalties against journalists, used to sideline ‘other voices’ through treason charges or other silencing measures, are also part of this pattern. The recent HRCP report Harsh Sentences: The State of Freedom of Expression in 2022–24 states that 22 journalists were killed, tortured, or unlawfully detained between 2022 and 2024. The social media platform X (Twitter) was blocked nationwide in 2023–2024; 1.3 million URLs were censored for being ‘anti-Islam’ or ‘immoral’. Top TV channels elevated pro-state ‘B-grade’ anchors (19 identified) to prime-time slots. TV channels owned by politicians (e.g., Aleem Khan’s Samaa TV) received state favour, while critical outlets lost advertising revenue. Laws like PECA (amended in 2023) criminalised dissent as ‘anti-state’, with its recent amendment representing a new move towards completely state-controlled journalism.

There are several recent cases where individuals from different classes narrowly escaped branding as traitors. From signing the affidavit of young poet Afqar Alvi to silencing various second- and third-tier singers, followed by media campaigns of a certain political class condemning ‘political others’, we witness how political opposition is suppressed by the powerful in Pakistan.

It is politically economical to exploit such emotions for temporary gain, but the social, political, and institutional consequences are grave. The political cost is abundant. When such conduct plagues a state, it becomes normal to witness vandalism, separatist movements, and even insurgencies that cannot be prevented. Complete political denial of others damages the democratic prestige of a country. We should be mindful that democracy is not a hundred-metre sprint, but a marathon requiring much more energy to make it functional by rejecting all forms of political insanity.