It starts as a slow trickle crawling up your spine—each sharp nail leaving a trail of guilt running down your back, like your very existence is a sin. You feel eyes boring into the back of your skull even when you’re alone.

“Even the walls have ears”, is a phrase all South Asian children have heard one too many times in their longevity. We grow up as spectators to a show, one for the amusement of our audience — constantly keeping us under surveillance, judging and scrutinising our every move. They come in many bodies, ranging from aunties who stick their noses where it’s unnecessary, uncles who tend to feel the need to comment on almost everything with their unsolicited opinions and neighbours with their binoculars made of shame. This can be categorised as one of the many aspects of Desi surveillance culture, marginalised as safety.

Mothers become matrons, carrying out rounds of phone snooping with the same old dialogues of “it’s for your good”. Practising emotional interrogation armed with weaponised incompetence: who were you texting? Where were you going? What friends? Privacy becomes an illusion, one fragmented enough to be used as ransom; every step is traced through applications, every location checked like clockwork to ensure the youth does not step out of line or bring shame to the family name.

The interrogation takes another round, headed by the father with his unofficial league of izzat keepers: the brothers, male cousins, and uncles. Every sliver of detail is extracted to the depth and closely analysed by watchful eyes. If you have a phone, you’re already one step in the wrong — your screen becomes foreign, your friends a bad influence. So is love, as tracking gets infested with passcodes and Life360 notifications become reflex.

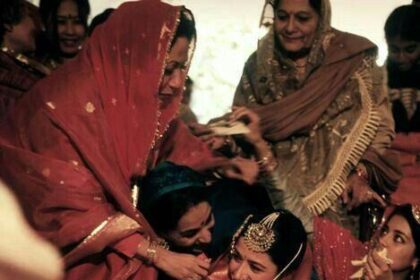

The watchful gaze lingers even in public; young minds are fed eternal warnings of “log kya kahenge?” (“What will people say?”), a simple statement meant to disarm many, as fear is used to justify protocols. Rules are dished out instead of dinner, and truths of how modesty is their only refuge are digested, mixed with the acidic tastes of shame purging out at the core. You are handed a script to follow word for word: how to sit, how to eat, how to talk, how to laugh, and how to reduce your personality until you are simply a vessel. Girls’ izzat )honour) is said to be delicate; thus, they are tamed and domesticated into good daughters.

Where do the rules go when boys stay out late till dusk, while girls are taunted for even stepping foot into their tuition centres without a scarf on their heads? Survival becomes their main aim in life—every step becomes calculated for the Doomsday that would descend if a man touches her. She would taint the family’s reputation; it wouldn’t matter that she got hurt, because what is more important is that they got humiliated.

It’s no longer about protection, but possession; her safety doesn’t matter as much as her obedience, and her pain becomes secondary to pride for what is a little ruin of hers—to save their name. The only viable option seen is marrying their daughters off, making them someone else’s burden: a dog on a leash handed to a new master. The eyes watch through a new lens adorned by mothers-in-law and husbands.

Concerning the Oxford dictionary, the Panopticon effect is described as “the psychological impact of constant surveillance”, where individuals develop a certain tendency to modify their behaviour when they believe they are being watched even though there would be no concrete evidence of such. The effect bloomed from the Panopticon prison design, where cells were arranged in such a manner that they formed a circle around a centre tower, allowing the guards ample space to keep an eye on the inmates without themselves being sighted.

In this case, eventually, the eyes hold you captive, a chilling presence whispering in your ear—“I see you”—so you learn to adapt. You rehearse your answer to every question and let yourself fall behind; thus, when the steps get closer, you already start your routine with monotony: delete the chat before it sees the light of day. The surveillance inhabits a deep crevice of your brain; you lower your voice when you laugh, you cross your legs and sit like a lady, you keep your head down in front of the men, you second guess a selfie. You fix your tone before sending a text to your friend because what if they catch you? Even when all you do is exist, the little voice rings out, “Are you existing correctly?”

Our Desi surveillance culture has evolved enough to forge our own panopticon with modern-day tech, yet the same old piercing gazes fixate on one child and then another. Instagram stories are monitored religiously, while search histories are scoured through in hopes of finding anything that might label them as suspects. A certain screen time limit is enforced on these gadgets, for if it is over, you hand them over, no questions asked. Quite ironic, isn’t it? How we progress with our newfound tech yet use it to implement our old-school rules.

So they learn to hide, to shield not only themselves but also the small bubble they created guarded by the eyes. The tower no longer looms in the centre of a prison, it lives in our phones: our apps, every notification; constant scrutiny comes at a cost. Children start to lose themselves in the fear of being watched, which takes a toll on their mental health. Anxiety claws at the pits of their stomach like a raving beast snarling at every mundane task while their own body starts feeling foreign to them—a machine operating on borrowed time. The inability to express themselves, and to let another person in their sanctuary, compels them to hide away who they truly are. They find their relations becoming one-sided, each attempt shot down by their secrecy, trust issues spiralling and consuming them whole, for what would they see? Could they peel away each layer and find what lies underneath? Who do they become when no one’s watching?

Instead of control becoming the main pillar of our desi households, why not replace it with trust? Where you can have full faith your child won’t ever do anything that could potentially lead to humiliation. Small texts don’t indicate whether she’s going to run away from home, or leaving her family’s reputation in tatters. Because bringing shame is not a girl’s default setting. An idea our parents need to digest is that giving our children decent amount of privacy does not add up to rebellion; a bit of fresh air in the lungs will not pollute them to turn against their very homes. Our children cannot breathe under a gaze so vehement; every exhale cannot be choked up with worries of what would they say if they saw me?

Their ears ring with the familiar lines of “It doesn’t matter to us, but what would they say?” Why should it concern us what they think? Everyone on this earth was put to live, so why should one do so and the other suffocate? Enough time has passed for our generations to realise love never comes in the form of tracking, phone snooping, or even the ping of location sharing; rather, love blooms from a trust that mends the broken cracks in each of us, spreading like vines tugging us closer to one another.

How many more shall we lose to the script of this play until we realise the audience is never truly satisfied?