Take a deep breath, dearest reader, as we are about to plunge into deep, ancient waters, literally. Water is one of the most important resources governing human life, shaping city layouts, and running ecosystems efficiently. Baolis, also known as stepwells, signify an innovative way of sourcing groundwater. Once acting as the lifeline of the Indian subcontinent, these marvels of ancient technology now remain as nothing but ruins. In this article, we will learn all about the Baolis of the subcontinent, ranging from questions like what they are and how they work to their unique design, the lore surrounding them, and what can be done about them today.

History and Background:

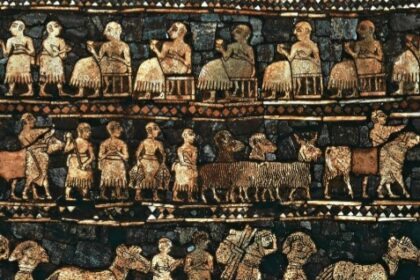

Stepwells symbolize the shared history between Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. They have belonged to the Indian subcontinent since the 11th century, when Mahmud of Ghazni began invading Northwestern India. At a time when kingdoms were popular, sultans and various influential people would commission architects and labor to build baolis. They aimed to seek a secure alternative to rain and river water for the purpose of fulfilling their people’s need for water.Baolis were especially common in the arid Northwest regions of India, where dry summers and droughts resulted in little to no precipitation. In these areas and seasons, baolis offered people an intricately designed, reliable water source many feet underground. Though some of the baolis were rain-fed and relied on the heavy monsoon rains in order to replenish themselves, most sought groundwater.

How Do Baolis Work?

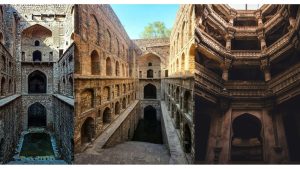

To build a baoli, a hole would be dug many feet under the soil until the water table was reached. There, an underground well would be constructed with a separate pool fed by a well, which was usually located adjacent to it. To keep the water from evaporating, the well would be hidden from the sun using a roof, with many steps leading down to the pool. The shaft above them was carved and adorned, equipped with colonnaded verandas and resting rooms. The well, pool, and steps constituted the entirety of the stepwell. Stepwells functioned to provide clean and safe drinking water to the people; this was apart from the many other uses of the baoli. The reason behind this was that the drinking water and bathing water were not allowed to mix. Therefore, the drinking water was drawn directly from the original source, the well, using a bucket and pulley system, while a separate area, the pool that was fed by the well, was used for washing clothes, bathing oneself, bathing one’s animals, and any other purposes. This system kept the water in the well hygienic for drinking and cooking purposes. The depth of the baoli, and the shade that the steps offered, allowed the temperature near the water to remain surprisingly low, drastically divergent from the temperature above ground.

The Uses of a Baoli:

Besides drinking, bathing, and cleaning their animals, the people found it convenient to use these stairwells as congregation points. They could often be seen lounging on the verandas and steps, discussing and gossiping, as people do. Women would bring their chores to the baoli and work in the cool environment. Kids would be running all over the place, bathing and playing. Within some baolis, mosques were built so that the Muslim residents of the surrounding area could pray in the cool atmosphere. Sometimes, Hindu women would perform their religious rituals in the baoli too. Baolis were the social and religious nucleus of the Indian subcontinent at the time. Interspersed across 9 centuries all over the Indian subcontinent, each of them featured a unique design.

The Architecture of the Baolis:

The structure and the architecture of a baoli hint at the era it was built in, hence reflecting the need and specialty of that region. For instance, the baoli of Nizamuddin Auliya reminisces about the Tughlaq era through its arches. Similarly, the baoli at Purana Qila in India was made mostly of quartzite stone found in Delhi, the city that it was located in. Another stepwell in Delhi, Gandhak Baoli, has arches decorated with incised limestone plaster, where the design is carved into soft, porous limestone plaster before it hardens. The result is a water-resistant and durable design, lasting for centuries. The Gandhak baoliis also distinguished by its name, which comes from the water smelling of sulfur (gandhak).

Baolis come in many shapes and sizes. The baolis at Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi, and the baoli of Sher Shah Suri, Gujranwala (Pakistan) are impressive circular structures, while the Gandhak baoli is rectangular. Some, like the one in Gujarat, India, boast helical staircases, while others are L-shaped, like the Rani’s baoli in Pakistan and the baoli in Red Fort, Delhi. While most of these structures speak of splendor, those built near inns had a much simpler design. These were made for travelers and hence focused more on utility and maintainability.

The Lore Surrounding Baolis:

It is nearly impossible for a historic landmark to exist without some kind of lore. Baolis are no different, shrouded by an air of mysticism and enchantment. A baoli in North Bengal, Bangladesh, is called JiyotKundi, which means the well of life. The Baoli of Nizamuddin Auliya in India was built in the night as SultanGhiyas Uddin Tughlaq was building his citadel and forbade laborers from working on any other project during the day. When the Sultan found out about the nightly construction of the baoli, he stopped the supply of the oil that the workers were using in their lamps. One version of the story says that the workers used the water of the well to light their lamps. Another baoli in India, the Agrasen baoli has black water, which is known as suicidal black water. It is believed that the water is haunted and draws people towards it, luring them into drowning themselves in it. Spine-chilling, I know.

The End of an Era

The stepwells fell into disuse after a rich history of 9 centuries. This came about in the 19th century when the British took over the Indian subcontinent as they believed baolis to be unhygienic water sources, preferring the use of a pipe-based water system. The aftermath is what we see of baolis today. India protects and preserves most of its baolis under laws like the Heritage Conservation and Preservation Act (2010) and organizations like the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH). The baolis in Pakistan, however, have been neglected and have, in turn, fallen into ruins despite existing laws like the National Fund for Cultural Heritage Act, 1994. Baolis offer a potential tourist point and remain a strong symbol of our culture and heritage. They can also be renovated and reopened for public use to solve the growing water crisis in the three South Asian countries.

Stepwells, or baolis, were considered the hub of social life in their times. Although they only remain as ancient ruins and garbage dumps now, they speak volumes about a time and people before us. Baolis are a symbol of the ingenuity and grandeur of the various Sultanates of the Indian subcontinent. Spread all over Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, these architectural marvels are a testimony that our roots are connected.