During the 17th century, the world was a mess, mostly ruled by kings and empires that had been running for centuries. Among them was the French Empire in Europe.

Run by the royal family, France was nothing more than an empire in decline, although still ignorant enough to stay loyal to the miserable yet royal family. Louis the Great, or Louis XIV, during his life, passed on his succession to a five-year-old heir, who was later named Louis the Beloved or Louis XV.

After reaching maturity at age 13, according to the norms of the time, he took over sole control of France, continuing to ascend the French Empire. He decided to join Austria, leading to the infamous Seven Years’ War on the French and Indian fronts. These campaigns cost the empire dearly in both its treasury and social peace, yielding little territorial success in return. France continued to decline both economically and socially.

On the other hand, the monarchy was busy enjoying a lavish life in the Palace of Versailles, situated in the countryside. The palace itself was—and still is—a symbol of incomparable luxury and royalty, marking a reign of injustice toward the common man in the most notorious ways.

King Louis XV was still respected and loved by the common people due to their religious beliefs regarding the emperor’s spiritual importance. He was named Louis the Beloved for that reason, but he could not care less about his empire or the well-being of the people. He continued to sideline their needs and lived a life of misery, making failed decisions and launching ineffective campaigns, which fueled growing hatred toward the monarchy.

His successor, King Louis XVI, was controversial from the start and ultimately proved to be the last king of the French Empire. He ascended the throne after the death of Louis the Beloved. Louis XVI was married to Marie Antoinette, an Austrian princess hated by the French due to the losses suffered in the Austrian-French coalition during the Seven Years’ War.

Louis’s early rule consisted of attempts to reform the government and establish social peace. He attempted to tax the rich and decentralize power but was abandoned by his assembly and allies in government. The young king now showed all signs of weakness. A famous incident occurred when one of his ministers resigned due to rising social chaos and the government’s incompetence. Louis, too, spoke his heart and wished to retire, but he was shackled to the monarchy, forced to lead a broken empire.

Though his reign had some notable events, such as the Treaty of Paris, which ended the long-lasting war between America and Britain—with France allying with America to secure victory—the local population had little interest due to rising inflation and worsening social conditions.

During a period of food scarcity and particularly poor harvests, uncontrollable riots erupted, weakening the government. The storming of the Bastille was slowly putting the final nails in the coffin of the Ancien Régime, a term used by journalists to refer to the old monarchy-led system in France.

The riots were devastating. Civilians, who once considered rebellion an act of treason against God, now invaded and looted the homes of the rich.

By the 1790s, the monarchy had come to an end, and the king was forced to sign a new constitution, which included the Charter of Human Rights. One of the last encounters between the king and his people played out like a dramatic battle scene—a war veteran, leading the king’s carriage, held a long, shiny sword as they faced millions in Paris, challenging anyone to dare touch the king.

Nevertheless, Louis was eventually forced to sign and accept the new assembly. By then, the country was nothing more than a conquered yet devastated empire, undone by its own people. The new government, chosen by the people, also proved incompetent in addressing the problems of the common man. This led to the declaration of martial law and the invention of the guillotine—a modern method of execution—during an era already filled with gruesome and violent deaths.

Martial law resulted in nearly 17,000 deaths. Even speaking against the current weather was considered disrespectful to the government and an act of treason, punishable by the guillotine.

Maximilien Robespierre, the ruler under martial law, continued to blame the monarchy and foreign powers for conspiring to create social disorder and hardship. This led to the execution of King Louis XVI and his wife. Marie Antoinette was accused of molesting her own son—an accusation that, according to most historical sources, was a deeply disturbing and disgusting part of the revolution. Her son was forced to be present in court as a victim. Marie, who had remained silent after the loss of her husband, could not stay quiet this time. She condemned the accusation as an insult to every mother, yet she accepted her fate and embraced death with honor.

Her husband, prior to his execution, also walked to his death like a king, shedding his earlier image of weakness. In his final speech, he stated that his trial was unfair, yet he would accept the decision with grace if that was what his people wanted from him as the last emperor of the great French Empire.

Robespierre later met a gruesome death, locked in a room before the government handed power over to a weak administration.

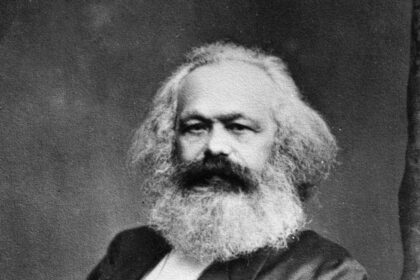

It was indeed a failed revolution of its time. However, the concept of equality and human rights—though existing before—was now practically inspiring great thinkers like Karl Marx, who later presented the idea of a bloody revolution and communism.

As for France, a child born on the island of Corsica was destined to be a general for his country, fighting and weakening its enemies during its worst times. Napoleon Bonaparte—probably the greatest general in both modern and ancient history—took over France and led the country to its destiny in the most glorious ways.