Near the site of China’s first emperor’s mausoleum, tall rows of clay warriors stand ready to charge at the command of their revered ruler. These terracotta soldiers were awakened from their slumber in March 1974 when a group of peasants from a drought-stricken village, while digging a well, unearthed their fragments. These fragments led archaeologists to discover what the world now calls the eighth wonder of the world. The discovery of these terracotta warriors brought ‘hope’ that it would finally help archaeologists and historians separate myth from fact regarding the history of the Qin dynasty—the dynasty that was meant to last centuries but ceased to exist within 15 years of the death of its first great emperor.

The question that now arises is: what happened to the empire that had such vast land holdings, consolidated the diverse ethnicities and tribes within the region, and gave us a close map of the China we observe today?

These 8,000 silent soldiers provided a much-needed bridge to close the historical inaccuracies within the accounts discovered from that time period. They assisted historians in understanding the military structure, armor, and weapon advancements of the reign of unified China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang. After viewing these silent warriors, two of the most pertinent questions that one may think of are why and how these life-like soldiers came to be. Though Qin Shi Huang’s reign is not known for generosity or forgiveness, these terracotta warriors can be seen as a deviation from the tradition of burying servants alive with their dead master. This deviation can be speculated to stem from his desire for immortality—one that has plagued many great men—and his wish for not only his servants but his entire reign to accompany him in the afterlife.

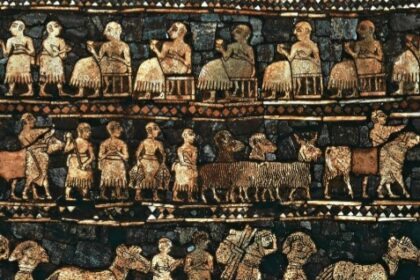

The necropolis of China’s first great emperor is said to be as vast as Manhattan. A prima facie observation of the terracotta warriors may lead one to believe that Qin Shi Huang’s rule was marked by an authoritarian military regime. On the contrary, when one looks deeper into the terracotta pieces found, one sees that these fragmented statues were not only military men but also included the emperor’s court personnel, such as officials, administrators, acrobats, horses, and animals. The addition of these figures in the lineup of individuals immortalized in clay to accompany him in his afterlife suggests that he found them to be an integral part of his regime. Hence, when we observe who these clay statues—meant to imitate his rule—were, we can speculate that even though he consolidated the scattered China with his army of 500,000 men, they remained unified because of his emphasis on administration. This speculation is further supported by his efforts to standardize weights and measures and introduce a common writing script for all of China. He is also said to have continued the construction of the Great Wall of China, the architectural structure most associated with Chinese identity.

According to an article in *Smithsonian Magazine*, the head of the mausoleum excavation team, Duan Qingbo, said:

“People thought when the emperor died, he took just a lot of pottery army soldiers with him. Now they realize he took a whole political system with him.”

The fact that a material such as terracotta was used instead of something more precious and everlasting like bronze suggests that the emperor cared more about the number of soldiers in his clay army than their quality. When one sets out to consolidate a landmass as big as China, civil and political unrest is bound to arise. Emperor Qin led his empire with a punitive approach, which meant that this unrest resulted in a crowd of prisoners in captivity who could be used for hard labor. Archaeologists have speculated that they must have taken an assembly-line approach, where artists from all over the vast nation oversaw the project, and prisoners—much like in modern-day product manufacturing—created each part separately, such as armor, shoes, and weapons. In the final stage of production, because everything was made of clay, they could have been easily assembled with customizable heads.

One of the most striking characteristics of these silent soldiers is the individualistic features they possess—no two soldiers have the same facial features. One might think that these unique features meant they were portraits of Qin army soldiers or high-ranking officials. However, historians and archaeologists have argued that the unique features might not be portraits of individuals but rather a representation of a nation built on the unification of various tribal ethnicities.

Netflix released a documentary called *Mysteries of the Terracotta Warriors*. From the title, it appears that the documentary would be an exploration of the history of these clay warriors, suspended in time to accompany the great monarch in the afterlife. However, the title feels more like a hook to get viewers to watch, as the documentary only briefly touches on the history of these warriors and what their discovery meant. Instead, it tries to link the new exhumation of the supposed son of the great Emperor Qin (the identity of the remains found was inconclusive) with the destruction of these warriors. The documentary fails to unearth any new evidence that might aid in understanding the mysteries that lie within the tomb.

The destruction of the terracotta warriors has long been linked to the devastation caused by rebel forces after the death of the Qin dynasty’s second emperor. The walls where this sleeping army was found, along with the fragments, all show signs of fire damage. This has led archaeologists to believe that the fire caused the wooden beams supporting the roof to collapse onto these proud-standing warriors, shattering them to pieces.

The necropolis remains the undisturbed resting place of the slumbering emperor, beneath a forested hill surrounded by cultivation. Out of respect for the imperial resting place, the site has never been excavated. This means that descriptions written half a century after the death of Emperor Qin—about the tomb containing a wealth of wonders, including man-made streambeds contoured to imitate the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, flowing with glistening, quicksilver mercury that resembles coursing water—remain unverified.