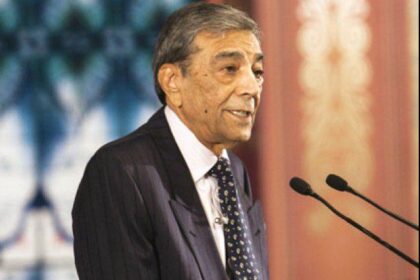

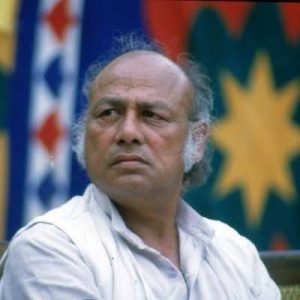

Hoshiarpur, literally “city of the alert,” is now an unassuming city and district in Indian Punjab. But in 1928, Habib Ahmad Khan was born. Though one would not have known at the time the fiery poet and orator he would become.

In the annals of Urdu literature, he is known better by his Nomen Calamum, Jalib. And to us in Pakistan, as the Shayar-I-Awam. An epithet given to him by the veritable giant that was Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

In the rich tapestry of Urdu literature, Habib Jalib occupies a unique and indomitable position. A revolutionary poet, a relentless critic of tyranny, and an unflinching voice for the oppressed, Jalib’s life and work serve as a testament to the power of poetry as an instrument of resistance. His words, brimming with passion, wit, and an almost divine sense of justice, became the battle cries of movements that sought to challenge and dismantle the forces of oppression. Rejecting the esoteric and ornamental style favored by many traditional Urdu poets, Jalib’s verse was characterized by simplicity, directness, and an almost conversational tone. This made his work accessible to all and allowed him to forge an unparalleled connection with his audience. On many occasions, some of which (we are fortunate) have been preserved on camera, Habib could be seen and heard standing amongst groups of the admiring youth, melodiously delivering his withering commentary.

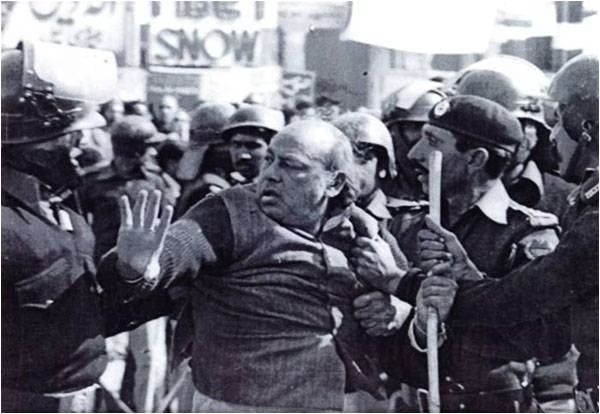

Jalib’s fiery words earned him admiration from the masses but also the ire of successive governments. He was imprisoned multiple times for his uncompromising stance. Yet, these incarcerations only seemed to strengthen his resolve. His poetry from these periods reflects both his personal anguish and his unwavering belief in the power of collective struggle. Jalib’s poetry exemplifies the lyrical beauty of the Urdu language. Its cadence, the interplay of soft and hard consonants, and the natural flow of its meter create a mesmerizing effect. Jalib leveraged these innate qualities of Urdu to craft verses that were both moving and militant. His mastery of rhythm and rhyme allowed him to create slogans that were as memorable as they were meaningful.

In one of his many memorable verses, “main nay uss se yeh kaha,” Jalib encapsulated his defiance and the universality of resistance; a translation of this poem is as follows:

I told him,

You are the light of God.

You have wisdom; you have awareness.

The nation is with you.

The salvation of the country

Is through your existence,

You are the morning star of a new dawn.

After you, there is night,

Those who speak,

They are all racketeers.

Take their tongue away.

Choke them by their throat.

I told him,

Those who were proud of their speech,

Now they are silent, their tongues extended,

There is peace in society.

An unparalleled difference,

Between yesterday and today,

They are imprisoned at their own expense.

People are under your rule.

Clearly, he was fearless in his blistering reproach of the sycophants that arise around every powerful ruler. Jalib’s poetry was a dagger aimed at the heart of authoritarianism, but it was also a balm for the oppressed, offering solace, hope, and the promise of a brighter future.

Jalib saw the Pakistan he had dreamt of in the euphoria of independence slip away before his very eyes. It is said that a man mourns his country till the day he is buried. In the case of Jalib, one is almost grateful that he did not witness the turns for the worse our beloved Pakistan took following his death.

His writings are as eloquent a criticism of corruption, sycophancy, religious extremism, and economic marginalization as the country has ever produced. Regrettably, the Pakistan of today is Jalib’s darkest phantasms made manifest.

Though one encounters increasingly few who could sing the entirety of Dastoor by heart, one encounters fewer still who understand the importance and meaning of such historic articles of shared culture.

Globalized and overstimulated, “Gen Z” by and large finds little time to embrace its own culture. When the political climate of nations that lie far away and insulated from the “mighty” Western powers is judged by their crop of youth through the praxis of alien societies, one need not wonder as to why the climate in the country is so toxically charged. Whatever his personal political ideation, the fact remains that the work of Habib, and that of others like him (though you would be hard-pressed to find any), forms not only a rallying cry for progressive movements but also a window into the heart of a culture’s idiosyncrasies. Without a firm grasp and wholehearted embrace of such works, our political and social culture is doomed to become more and more alien to that of our forefathers. And not necessarily for the better.

Nowadays one finds absolute vitriol being leveled against any and everyone for simply disagreeing on a particular topic. Gone are the days, it seems, when the likes of Habib would pen such eloquent disagreements that they would ring true across borders and generations.

The Shayar-I-Awam remains relevant to this day. Perhaps more now than he was before. If our generation is to achieve the level of awareness and political understanding that is the need of the time, then perhaps it is wise for us to study men like Jalib and escape what he called the Gumbad-E-Bedar.