Why is international law so weak? The question itself is not new; in fact, it has been around for quite some time. As a student of law, I started thinking about this when I got some exposure to international law through moot court competitions. I soon found myself asking my seniors: why is this domain of law so weak when it comes to implementation? And now, almost two years later, I find my juniors asking me the same. The pattern hasn’t changed, and neither has the answer. While in theory it appears noble, in practice it seems devoid of influence and bends to the will of power. Over time, one observes that institutions like the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and International Criminal Court (ICC) only come forward as a tool of the Western hegemonic powers, safeguarding Western interests and failing from time to time in holding the West accountable for its unacceptable practices.

In earlier times, there was no common international framework between the nations. A development was seen as Europe came out of the Thirty Years’ War and the Treaty of Westphalia was signed in 1648. The principles of state sovereignty and non-intervention emerged, which have become the cornerstones of modern international law. Although this development was confined to Europe, over time it made its way to the global stage with the rise of nationalism and the formation of sovereign nation-states around the globe.

However, no legal framework existed to protect these principles. Therefore, after the devastation of the First World War, the world realised a need for a common global framework in place to ensure cooperation and peace among the nations and to avoid the failures that led to the First World War. Hence, the League of Nations was established.

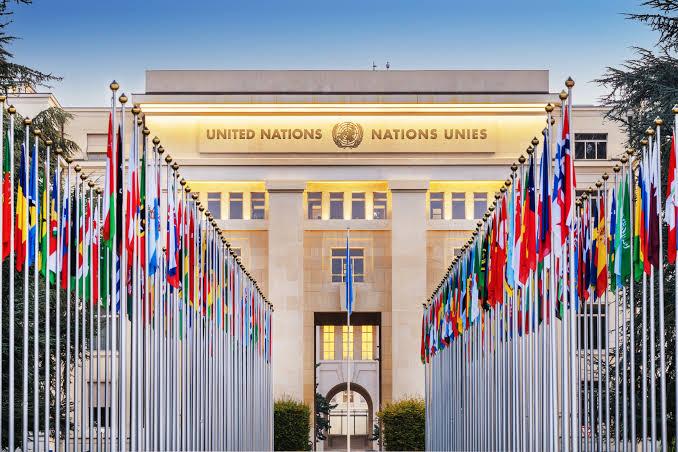

This institution was the first formal step towards the creation of a universal international law, but due to its limited powers and ineffectiveness, there was a need for a stronger international body after the Second World War, which led to the establishment of the United Nations. The purpose of which was to promote international diplomacy, peace, and facilitate cooperation. It provided a platform for the nations around the globe to come together and resolve conflicts through dialogue so that devastating events like the World Wars wouldn’t repeat. Therefore, the ICJ was established in 1945 to settle legal disputes between states so that nations would resort to such platforms to resolve disputes rather than going to battlefields.

Similarly, crimes like genocide, aggression, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other inhumane acts became punishable, with nations agreeing to punish the aggressors committing such atrocities. Implementation of this can be seen through the establishment of tribunals, such as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), which were established to prosecute serious violations of international humanitarian law (IHL) in their respective regions. But still, there was no global permanent platform to prosecute these offenders, so the International Criminal Court was established in 2002. Since its inception, the ICC has prosecuted many criminals for various crimes, from leaders of their nations to military generals.

While all of this may sound good on paper, in fact, international law may even seem to be doing what it was supposed to do. However, closer inspection would lead to the realisation that these are mere smokescreens. There are structural weaknesses of international law that often emerge. International law can be defined in a single line as “the body of laws that is enforceable on a state only when it chooses to accept it.”

But what if a country refuses to comply? In such situations, international law seems to be like a giant without arms and legs. It often lacks enforcement in these situations, as there is no international enforcement body that would make these nations accept the decisions by these bodies like the ICC or ICJ.

Similarly, the absence of an enforcement mechanism isn’t the only flaw. The United Nations was built as a body of international dialogue. The question arises: what if nations don’t follow the resolutions of the General Assembly of the United Nations? Well, nothing would happen, as these resolutions are merely of advisory value. These are mere advisories to these nations, and they wouldn’t be held accountable for the refusal to comply with these resolutions.

One can argue, though, that the General Assembly resolutions might be of advisory value, but the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions are binding on UN states. But these resolutions can only be implemented with cooperation among the member states. So, the issue exacerbates when the permanent member states (USA, Russia, China, France, and the UK) use their veto power to stop the UNSC from passing resolutions against their allies. This was seen in the Security Council meetings last year, when the matter of a ceasefire in Gaza was brought and America kept using its veto power to save its closest ally, Israel.

Moreover, the ICC has continuously been used as a neo-colonial tool by the West, mostly seen prosecuting those leaders who are not complying with Western agendas. Those who are friends of the West are often excused, with their violations often being overlooked or ignored. The court is often seen being biased against African leaders, as most of the convictions are against them.

Furthermore, another systematic flaw is that arrest warrants are given by the ICC against people suspected of violation of IHL, but these people are not even arrested in many cases. As the court doesn’t have its own police and relies on member states to execute the arrests, the states often refrain from doing so for diplomatic reasons. For instance, take into consideration the arrest warrant against Vladimir Putin in 2023 or against Benjamin Netanyahu in 2024. Both of these leaders were not arrested and the arrest warrants remain impotent.

Similarly, many Western military actions, such as U.S. operations in Vietnam, Iraq, and covert operations in South America, were never treated as violations by the UN. The USA killed around 500 unarmed civilians in the My Lai Massacre in Vietnam, which constituted genocide, but was overlooked. Similarly, military operations of the USSR in Afghanistan, NATO’s actions in Kosovo, or USA’s drone attacks in Pakistan were rather labelled as acts of counter-terrorism.

Furthermore, the Western hegemonic powers have overwhelming influence over the international institutions. They just simply seem to be above the law. A clear example of this is the “American Servicemen’s Protection Act of 2002”, an American legislation that allows the USA to literally attack The Hague to free any American personnel who is detained by the ICC.

So, the question is not only why is international law weak? The question also is: why isn’t it just? Why isn’t it fair? Why do the global superpowers always get to evade accountability but the smaller nations are made to face the shorter end of the stick? And ultimately, the question is: until when will international law remain weak and used as a neo-colonial tool being applied selectively?