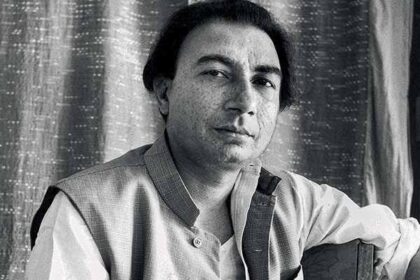

Once upon a time, there lived a young boy named Iqbal Masih. He came from a poor family in a village on the outskirts of Lahore—Muridke—where he lived with his parents and younger sister. Sadly, one day, his mother fell ill and needed costly treatment. His father was using drugs, and his mother couldn’t work anymore. So, the boy’s parents decided to sell him to a carpet factory owner, Ghullah, where he would work to pay off their debt with interest (this is called peshgi in the local language). Iqbal was five years old. He didn’t know that his childhood had already been bartered.

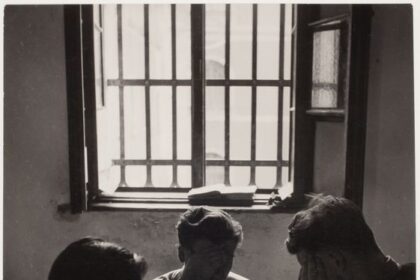

The boy was beaten, tortured, and made to work for twelve hours each day, seven days a week, with only half-hour breaks. Many times, he would be woken up at midnight because he had to work on a new order. He was not given proper food because carpet weaving required small fingers. He and his friends tried to run away, but whenever they returned home, the owner would be waiting for them—furiously—to drag them back.

One time, the owner tied the feet of Iqbal’s friend to a ceiling fan and left him dangling upside down as punishment for taking a day off due to fever.

Iqbal, the Freed Boy

Until one day, Iqbal had had enough. He decided to run away and go to the local police; of course, the police would do something when they heard how his owner had tortured his friend, right?

Alas, the boy didn’t know that the police had already sold their conscience in exchange for a little money. They took the little boy back to his master: “Keep this traitor and never let him run away again.”

This incident didn’t break Iqbal’s spirit. He had become fearless.

One morning, Iqbal saw a truck arrive, its back filled with children who looked just like him—tired labourers. One of them told him they were going to a BLLF meeting where they would be freed. The boy didn’t need to hear it twice. He quickly hopped onto the truck, which took them to a gathering of the Bonded Labour Liberation Front, an organisation working to free child labourers.

According to one of the officials, Iqbal was wheezing like an old man when he reached the meeting place. Such was the state of his deteriorated health. He looked like a six-year-old with a childlike, squeaky voice, despite being double that age.

“According to the law of the court, no child is allowed to work,” Ehsan Ullah Khan spoke into the mic. “Go and tell your masters we will come with lawyers to free all of you.”

Iqbal’s eyes sparkled. After the meeting, he went back to his village, but the light in his eyes remained—for now he knew he would be free.

Some days later, officials from BLLF came to his village, and that was the last time Iqbal ever had to work as a bonded child labourer.

Iqbal, the Activist

Now a free boy, Iqbal began his formal education. He was a quick learner and an eloquent speaker. He completed four years of education in two years. He told other kids in his village that they were not required to work under the law of the country. The children grew courageous; they began to leave labour.

However, some people in his village were irked. They didn’t want to lose their labourers because it meant losing income.

But Iqbal was fearless, confident, and purposeful. He couldn’t be stopped.

Iqbal’s voice crossed borders. In October 1994, he was welcomed in Sweden, where he spoke about child labour and the plight of the children trapped in it. Newspapers wrote about him, and he appeared on TV programmes. In December of the same year, he travelled to the USA, where he was declared ‘Person of the Week’ by one of the largest TV networks. Reebok awarded him for his relentless fight against child labour.

Iqbal, the Targeted

On Easter day, Iqbal came home. His cousins decided to take him to the fields in the evening, so they all sat on a bike. It was dark, and the journey was long.

Some time later, they all heard a gunshot.

Iqbal had been targeted.

Iqbal had been shot dead.

Nearly one in every ten children are forced into child labour worldwide.

When you give birth to a child, please bear in mind that this is a precious life that didn’t ask to be born. You decided it. You are responsible for it—not vice versa.