As her bicycle spokes serenaded the wind, Javeria felt that disquieting crackle all around. The blaring summer sun had simmered to a golden hum as the orange syrupy sky whispered tales long forgotten. There were green vegetative fields, with the occasional yellow mustard on her left side and the hubbub of a Soviet-style business district climbing atop the red brick house with moss and ivy encircling each inch.

The incidental street vendor chanted a luring proclamation as Javeria wondered how long until the university sold the last of their green fields to a corporate tycoon. It was the last green spot in what used to be “the city of gardens”, making it an evening ritual for her to cycle past the remains of what the proletariat wasn’t supposed to remember. Today, though, there was an urgency to her pedalling as sweat cascaded down her neck and made her hands lose their grip.

Nasrullah Khan Sahab—her grandfather—was coming over after forty years of absence. She had obviously never seen him, but he was one of those mythological figures that lurked at the periphery of life, embellishing your heritage with mystery in spite of the mundanity of habit, trying to enter those tombs where fairies, jinn, dragons, gardens, vampires and love resided.

Her mother used to tell stories of his conquests to her when she was a child—how he defeated a grotesque giant who suffocated the waterfalls so that humanity would die of thirst or the way he tried to build a wall around the two brother states so that the world wouldn’t tear them apart—but we all know that fraternal devotion is a red flag to the bull of global governance that chases it until it breaks it down. The brother states were deliberately splintered, and her grandfather’s sin was trying to sew the tapestry of their love back together. Javeria’s mother stopped telling the stories; the nation forgot its hero, but there remained a sizzling luminescence in her blood that evoked an inexplicable sensation telling her that something remained amiss. Something that left an incompleteness in her life that she tried to quench by chasing mustard fields and sunsets.

As she chained her bicycle in the backyard, she felt a shiver run down her spine. Step by cautious step, she entered her house that resembled a mortuary with the same air of mourning hanging about densely. Night had spread its sable veil across the sky, and Javeria’s mother couldn’t afford to be generous with electricity, so the only light in the living room was coming from the TV, which blared nescient to the old man sitting in front of it.

The blue bled into the green, but his eyes remained unfocused and hollow as he stared into nothingness. What did paralysis feel like? What really was betrayal? Javeria felt like someone had taken an axe to her resolution. She could’ve sworn to have heard the guffaw of fate having a delightful time witnessing its handiwork. Was this the man she had unconsciously idealised all her life? Was he the sole reason for her survival in a world so out of joint and tainted—that its putrid stench couldn’t be concealed to her and her alone? “Who brought him here, Ma?” whispered Javeria to her mother, who was entering with soup and some chopped mangoes. “We weren’t supposed to know the specifics, so three men in suits left him at the threshold without a word”— Javeria chuckled internally. Wasn’t this the oldest trick in the book, to replace the uniforms with suits and pretend no authorities were ever involved, that four decades of precious life weren’t just wiped away from existence altogether? She went and quietly sat down next to him on the floor. His eyes, seeing the unseen, looked past her.

All our lives we anticipate certain significant moments to appear blaring exultance and echoing finality. This moment didn’t feel final to Javeria, who spent days sitting next to her grandfather, waiting for a sign, a gesture, a code, a murmur—something to help her spiral down the enigmatic path of hope.

He was back to reading on the balcony at dawn. Without a word uttered, he would become one with the written words. “Darling, go clean Aba’s room, collect all the old newspapers and throw them out before they attract a torrent of termites,” said Javeria’s mother, who was preparing to leave the house for the post office where she worked at the reception. “Will do!” exclaimed Javeria, who tiptoed to his room, expecting him to be asleep but found his shadowy form scribbling in the dark. Startled—she rushed to illuminate the oil lamp.

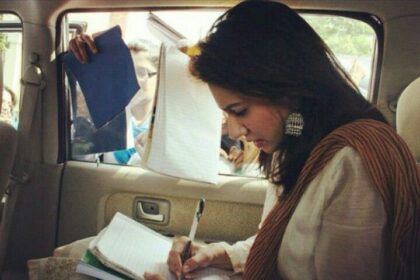

As the fiery flame fell onto his desk, it revealed stacks of newspapers with a maddening clutter of words in a dialect long dead. A lot of dots on rounded figures and italicised slants. It resembled something of the modern Arabic alphabet, but she couldn’t read it. “Nana Abu, what is it that you’re writing?” she cautiously enquired, but all he did was gaze at her as if she was to blame for ruining his reverie. As promised, she started tidying up the room and found reason enough to gather all the old newspapers which had similar codes (or so she thought) covering them.

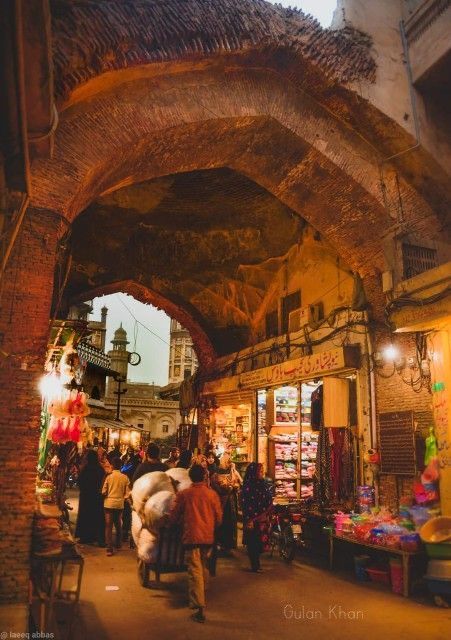

Unchaining her bicycle, which had remained stagnant for the entirety of a week, she strapped the newspapers on the inside of her sleeves so as not to raise any suspicion—having an ex-convict at her house was more than sufficient. Lightheaded and giddy, she pedalled past the woman on the sidewalk who wouldn’t stop singing, the boys who played cricket without any rules remaining, the barber whose roof was the sky and mirror was the canal, the flower shop that chose to sell gaudy plastic plants and the jeweller that thought fish bone jewellery was the epitome of luxury—to reach a secluded nook of this busy city where the only sound remained the rustling of pages and whistling of the kettle as it brewed the only cup of Kashmiri chai in the country. This was the house of an old woman who was so old as to not even exist in the government’s registry. To the few who knew of her existence, she was “Ustani Sahiba”—no one knew her actual name or where she was from, only that she was a river of knowledge. The house had a wooden door painted olive green with a brass knocker, which Javeria used to beckon the woman out of whatever new facet of research she must’ve been absorbed in. “Oh, sweetheart, how I missed you! Come in. Come in. Yes, sit right there; I’ll get you some of the halwa I’ve been cooking, and no, don’t make that face; I actually do cook when I feel the need to.”

And there it was, the warm house with its plush Persian carpets, Turkish lamps, Chinioti furniture and Renaissance-style paintings. Although they weren’t related, Javeria felt more at home here than anywhere else. This place was a sanctuary for dreamers and rebels alike who were allowed to read banned books, try foreign recipes and watch black-and-white movies in tongues they couldn’t understand.

“So how’s your grandfather? They used to call him “iron-boned”. Does he still make the sun rise as he sits with his ink-stained hands holding the railing at dawn?” asked Ustani Sahiba as she handed the cup of tea over to Javeria. “Actually I came here because of him. There’s something I need help with. There is obviously a clandestine nature to my request, so if you’d allow me, can I shut the windows?” Gathering the affirmation, she quietly latched the windows and covered them with the amaranth velvet curtains. “There is a certain code he has been scribbling all over his newspapers in a manic state of urgency. The writing is in a language I cannot read, but it’s the only remotely coherent form of communication he was offered ever since he returned.” By this point the kind woman had already placed her glasses at the bridge of her nose and was taking the newspaper to her mahogany working desk, where a single glance at the writing made her shut her eyes, lean back on the chair and purse her lips tightly as if she was trying to rein in a scream from erupting.

“Oh… heavens… oh, darling. I had quite forgotten all about it. But really, they had forced us to—hadn’t they? This is Urdu—the language we fought to make our own, which they fought to wipe out. Your grandfather has written a single word over and over again. I can’t find the right alternative to translate it, albeit it’s sufficient for you to know that he is humming to resuscitate a sound that must’ve paved the path of destiny for him and countless wide-eyed youth like him. He’s trying to summon the hymn of universal identity. A concept so foreign to us—he is tormented by the music of the national anthem”.

Javeria felt a deluge of fragmented fabrics cloud her sanity; her eyes were wide open, but the shivering in her arms made her vision fade in and out. What did the national anthem even mean? All that she had ever known was a vague feeling that was evoked every time she heard what was defined as the sound of the national anthem, which morphed into whatever note was set for the moment.

Ustani Sahiba brought her ancient radio to play the national anthem on—but as anticipated, the tune which echoed through was a Punjabi song in a hoarse female voice which turned into the ice cream man’s coaxing jingle that strung into an unnamed folk song every time she blinked. Ustani Sahiba heard a different set of sounds; blinking at different or the same times didn’t make a difference, and stopping yourself from blinking only made your eyes ache because the trick lay in the psychological rewiring of humankind in a way which was beyond scientific research.

Eyes glossed over, a lump in her throat, murmured Javeria in resignation, “It is hopeless, though, isn’t it? How will I ever know?” But even as she said this, there was a crystalline resolve which would’ve made her chase the ends of the world because, for once, something had made sense in this nonsensical world.

“You might not want to hear this and feel the absurdity of it in your young mellow heart, but listen to your soul. The moment your skin breaks into goosebumps and the feeling of reaching home is felt at the melody of a song you’ve never heard before—know that it is the national anthem. An anthem that was chanted at the battlefield, warbled by the birds, sung by the multitude every morning, and summoned as a reinvigorating refrain at times of uncertainty.”

This was how Javeria found herself gallivanting the dark alleys of the city in search of a melody she couldn’t hear but could feel. What did that even mean? Was it the sermon of the yellow-cloaked monk or the clamour of a bereaved mother? Was it the chant of the students who had given up on protesting or the bus conductor announcing the departure time? These sounds so familiar yet strange didn’t stay long enough. Was the motive to find something that wasn’t ephemeral?

Months passed. Restless hiding her grandfather’s secrets, sleepless nights, and dizzying reevaluation of every auditory stimulus to the point of ultimate exhaustion. Every now and then, Ustani Sahiba’s soothing voice would creep out of some crevice, asking her to “listen to your soul”, sizzling the gilded golden of her blood, which she had inherited from the unlamented warrior who, knowing nothing, knew too much.

In a moment of mutinous motivation, Javeria decided to write a poem for her grandfather—a poem that she would knit on her own with the thread of the land she felt she had never seen. What if rather than writing about the country of the present, she wrote about the nation which existed only in stories? So that’s how it started—for every observation of the present, she inverted it to fit the old tales—the sullied ground of today became “Pak Sarzamin”.