Shortly after sunrise, we received the news that we had expected yet dreaded for the past few days. I was hit with denial, which turned into shock and distress as reality glared at me dead in the face in the form of a casket placed in the courtyard as my father brushed the dust off it. The tragedy had struck.

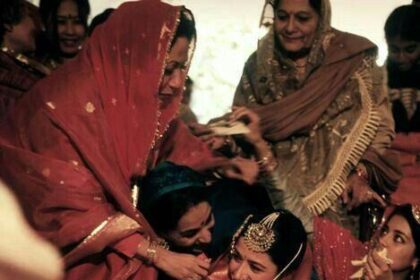

In a few minutes, women from the neighbourhood started pouring in while men gathered at the gate with my father and uncles. Some looked at us with compassion, while others just played along to a script that they seemed to have become well versed in and I was largely unfamiliar with.

White sheets were spread across the courtyard; the casket, now occupied, was placed in the middle, and manuscripts of chapters of the Holy Quran were placed on a table along with a basket of prayer beads. Someone also lighted a few incense sticks. Once the gathering had settled down, somebody started to cry. Eventually the voice got louder and more joined in. I envied their ability to cry at an elderly neighbour’s passing whom they did not really know properly, while I had not been able to shed a single tear. But when the faces that I was familiar with entered the scene, they were no different from mine, apart from a few always referred to as the “weak” and “sensitive ones”. The crying ceased, and some women started whispering.

“What kind of man is he? Instead of consoling his sisters, he’s all teary-eyed.” A sort of stillness then filled the atmosphere. Some sat and read the Quran, others did zikr, while a few talked. I heard someone comment on how unfortunate the deceased must be to have had such a silent funeral while he had such a large family.

The men then entered, the Shahadah was said and the casket was raised; that is when everyone broke down. Grief decided to make a show of even the strongest and the most composed to bring them down to their knees.

As we sat trying to get our heads around whatever had happened, we received an inquiry about when food would be served. Once the attendees had been fed and all the “mourners” had left, the family sat down to eat, because unlike popular belief, grief does not kill the appetite. After the Zuhr prayer, the courtyard was filled again, and we were met with constant questioning about the relatives from abroad who had failed to secure a flight on time.

“How unlucky; they could not even say a final goodbye to their father.”

I felt that this comment was unnecessary, but there was more to come. Someone complained about how the perfectly modest outfit worn by my cousin was unfit for the event because it was “too bright” and that she “should’ve been careful”. Another asked us how much we were planning to spend on the Qul, a purely cultural practice for the 40th day of mourning. I did not know how to respond to any of this, so I just shook my head and murmured the names of The Most Merciful as prayer beads slipped down from my fist one by one.

As the sun got dimmer, tea was prepared. It was insisted upon by the “women of the household of the deceased” to serve it to the gathering while we received a remark on how none of the family members bothered to ask the guests if they had been “fed well”, as if it was a walima. Thankfully, what followed was a group of side eyes, not at us but at those making the complaint. Humanity lives.

As sundown approached, women hastened to leave because a freshly departed soul meant that our house was “haunted” after dark. Again, some words of compassion and a pat on the back, and again, the oft-repeated emotionless script. Then once again, complete silence.

Suitcases were heard rolling. The gate opened. No greetings were exchanged. No questions were asked. The newcomers, visibly exhausted from the long hours at the airport and then the flight, just blended in with the rest. The soft sounds of sobbing broke the silence. Unlike another popular belief, while grief can certainly leave one sleepless, it does not rob one of tiredness, so some slept while others wept, and before we knew it, it was time for sunrise. I woke up to find the extended family WhatsApp group blown up with pictures and even edits of the deceased. Some close-ups of the face on some WhatsApp statuses. While this idea of mourning never resonated with me, my jetlagged cousin was absolutely horrified.

I did not have the strength to face yesterday’s drama all over again, but the elders had decided to keep the house open for “condolences” for three days, the length of three days determined from Islamic teachings.

Just after Fajr, trays of breakfast sent from different houses from the neighbourhood filled the kitchen. While it is generally seen as a gesture of goodwill, a common underlying belief is that for the first few days after someone passes away, the stove should not be lit in that household. Given how superstitious the second idea sounded, we just went along with the first. Soon enough, the same horrified cousin was dragged outside to “greet” the people who came to offer “condolences”. Some came and asked me if I had already gotten Sabr because I had not been seen crying for a while.

When my aunts asked to be taken to their father’s grave, it caused a stir within the gathering, with the majority saying that women cannot visit graveyards. I thought that we had moved beyond that as a society, but it turned out it was otherwise. The aunts still went, saying that nobody had the right to interfere. Again, a few whispers, a few side eyes, but eventually things cooled down as lunch was served again. My cousins from abroad complained about the lack of empathy. The same drill: some genuinely tried to console us, while others had found new topics of discussion—the Pardesis—so they whispered about how “modern” they had become and how they had raised children completely unaware of the culture, which was not exactly true, because they were only unfamiliar with our “mourning culture”.

I wondered how many deaths it takes for someone to specialise in the “grief etiquette” of our society——when to cry, when to serve tea, when to appear moved, when to be silent. But I also wondered something else: if we spent less time perfecting the performance of mourning, would we finally make room for the messiness of real grief—the kind that doesn’t need to be witnessed to be valid?

Maybe grief does not need rules. Maybe it just needs time, space, and the dignity to unfold—unwatched.