On the morning of June 7th, the day of Eid al-Azha, I woke up around the time of the Eid prayer and marched straight to the kitchen, because that was where I was supposed to be all day, more so than any other day.

Recalling Eid mornings spent at my parents’ house, I lit the stove with a heavy heart and teary eyes. I prepared breakfast and began cutting and chopping for the next meal, which would be expected soon after the sacrificial ceremony.

I’m not someone who runs away from responsibility or dislikes working in the kitchen. In fact, I put in my best efforts every single day to provide my family with the most delicious meals.

But the sadness came from the realisation that not just I, but millions of women across the Muslim world, would spend this much-anticipated joyous occasion toiling in the kitchen, soaked in sweat, without any help from family members or spouses.

And when the work is finally done, there’s seldom any energy or time left to get ready and actually enjoy the occasion.

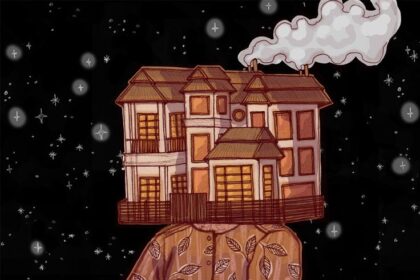

In Pakistan, women don’t only contend with glass ceilings in workplaces, rather they are hemmed in by walls and barriers of every kind, even within their own homes.

Look at most international indicators across multiple sectors, and Pakistan is statistically struggling near the bottom.

Our cultural roots go back more than a century, to when Pakistan was part of the subcontinent and a major part of that culture still remains unchanged: the part where women are expected to cook, clean, nourish, cater to, and comfort every single family member, entirely on their own.

The concept of shared domestic responsibility remains foreign to men in the majority of Pakistani households.

Hence, whenever a celebration approaches, women feel anxious, and sometimes even angry, long before the occasion actually arrives.

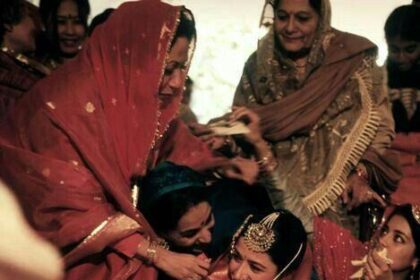

One such occasion is Eid al-Azha, celebrated on the 10th of the last month of the Islamic calendar, Zilhajj. A central ritual of this celebration is the sacrifice of an animal in remembrance of the Prophet Ibrahim (AS).

After the sacrifice, the meat is to be cleaned, packed, and distributed among family, the needy, and relatives. From weighing to washing, packing, and finally distributing, the entire process takes several hours.

And then come the guests. Women of the house are expected to prepare multiple dishes, barbecue, gravies, rice, and desserts, while also watching the children and managing everything else, as the men relax with laughter and drinks in the drawing room.

This exhausting grind doesn’t begin on Eid day. It starts at least a week before, with deep cleaning of the entire house, reorganising, restocking, and prepping the kitchen for the grand feasts. Nor does it end on the day itself, post-Eid cleaning takes just as much time and energy.

The point here is not to belittle the efforts men make outside the house to provide for their families but to highlight how deeply unjust it is to ignore the sheer amount of unpaid labour women perform, labour that is both unacknowledged and unappreciated.

And it’s not just housewives. Working women go through the same drill during holidays and again after returning from work.

Why is it that only men are expected to relax after office hours?

Why is it that only one gender gets to enjoy the holidays?

Where, and what, went wrong that led us to such an uneven and unjust distribution of responsibilities between the genders?

Across the world, rigid gender roles are slowly, but surely, disappearing. Men and women are expected to contribute equally to homemaking and homekeeping. Except in Pakistan, where years of chanting slogans and marching for rights often end in further silenced voices and more broken homes.

In my opinion, while it is vital to continue raising our voices and speaking out about these issues, it is equally important to begin involving our boys in household chores, just as we do with our girls. We should teach our sons to share the burden of domestic responsibilities and to care for the women in their lives, be it their mother, sister, wife, or any other woman.

It takes years, sometimes generations, to break a toxic cycle. But with consistent effort, it does break eventually.

This is a big fact that women want to change, but men don’t want to change. I should train my children in such a way that they don’t put their wives in these problems.