Arnold J. Toynbee once described Pakistan as the Eastern Crossroads of History. Anyone familiar with the region’s history, now one of the largest Muslim nations, would recognize this as true.

The creation of Pakistan from the ashes of the Raj was neither smooth, rapid, nor bloodless. A lack of narrative-building has allowed obscurantist and ahistorical claims to dominate discourse. The territories of present-day Pakistan, an ethno-linguistic kaleidoscope, have historically served as a junction between East and West, North and South. These lands have seen control shift from Afghan and Persian peaks to Hindu and Sikh juggernauts, and even Mongols, Arabs, and Mamluks. Understanding Pakistan’s identity requires viewing it through layers of shared historical experience.

One glaring omission in education and ideology is the understanding of Baluchistan, Pakistan’s largest province. Often seen as a hinterland, Baluchistan faces alienation from Pakistan’s politics. Few understand how Baluchistan became part of Pakistan. This lack of understanding contributes to the region’s alienation and perpetuates misconceptions about its integration into the Republic. By revisiting the historical narrative, we can better appreciate the province’s importance and the challenges it has faced since joining Pakistan.

The Eve of Freedom

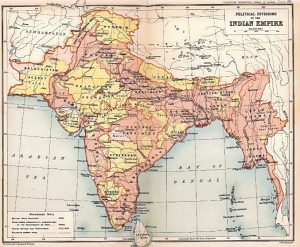

On the brink of independence, the British Raj was a patchwork of provinces, agencies, and princely states governed by differing treaties with Delhi and London. Baluchistan fell under the Baluchistan Agency, a legacy tied to Sir Robert Sandeman, who brought the region under British control through treaties like the Mastung Agreement. The agency included the Chief Commissioner’s Province and princely states such as Kalat, Kharan, Lasbela, and Makran. The Omani-owned Gwadar exclave, though not acquired by Pakistan until later, also features in this narrative.

Kalat, since 1666, saw itself as the supreme state in Baluchistan, ruling as a Brahui-Baluch confederacy under the Ahmedzai family. However, the Khan’s authority was often undermined by tribal autonomy. When partition loomed, the British unilaterally repudiated their treaties, effectively declaring the princely states independent post-independence—at least theoretically. This lapse of paramountcy fundamentally changed the dynamics between the princely states and the emerging dominions of India and Pakistan. For Kalat, this opened a brief but critical window to chart its own course, albeit under immense geopolitical pressure.

The Princely States Dilemma

Independence for princely states was unlikely due to Mountbatten’s insistence on geographical contiguity and the political pressure from Pakistan, India, and the U.S. States could choose to accede to Pakistan or India, but independence was not a realistic option. Mountbatten’s geographical criterion was pivotal to the accession process, though his role in partition—particularly Kashmir—is controversial. This insistence on contiguity ensured that princely states aligned their decisions with geographical realities rather than aspirations of autonomy.

Mountbatten’s legacy in Kashmir, however, is a withering indictment of his impartiality. His decisions directly contributed to the festering conflict that continues to this day. By favoring India’s stance and dismissing the political will of Kashmir’s Muslim majority, he ensured that the region would remain a flashpoint. The betrayal of Kashmir underscores the double standards that marked his administration of partition.

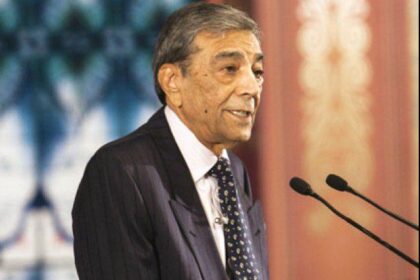

In Baluchistan, only the Chief Commissioner’s Province easily acceded to Pakistan, with its assembly voting overwhelmingly for the move. This was influenced by a spirited campaign led by Qazi Muhammad Isa, father of Chief Justice Qazi Faez Isa. Isa’s efforts exemplify the role local leadership played in shaping the political destiny of the region. Without his interventions, the narrative of Baluchistan’s accession might have been far more contentious.

The Kalat Conundrum

The Khan of Kalat, Mir Ahmad Yar Khan, and Quaid-e-Azam Jinnah shared a close relationship, with the Khan revering Jinnah as a father figure. Nevertheless, the Khan sought to preserve Kalat’s independence. Meanwhile, the rulers of Lasbela, Makran, and Kharan lobbied to join Pakistan, partly to gain recognition as independent of Kalat. Pakistan prioritized Kalat’s accession before addressing the others, underscoring the centrality of Kalat in Baluchistan’s political landscape and its symbolic significance for Pakistan’s territorial integrity.

Kalat’s internal dynamics were complex. Its ruling clique, appointed by the Khan, wielded nominal control. De facto, the princely states were independent, and tribal leaders retained significant autonomy. The Khan’s authority over regions like Makran was tenuous, as the British mediated disputes between the Khan and tribes. Despite the Khan’s resistance, Lasbela, Kharan, and Makran leaned toward Pakistan. Their inclination was shaped by a combination of historical ties, economic considerations, and recognition of the political realities of the time.

The Afghan connection adds another layer of intrigue. Historical ties between Kalat and Afghanistan created an avenue for Kabul to exert influence. The Khan’s overtures to Afghanistan for support in maintaining independence were strategic but fraught with risks. Similarly, Indian leaders, particularly Nehru, viewed Kalat’s potential independence as a means to weaken Pakistan’s western frontier. These geopolitical pressures compounded the challenges faced by the Khan in navigating his state’s future.

The Accession Process

On March 17, 1948, Pakistan accepted the instruments of accession for Lasbela and Kharan and recognized Makran’s independence from Kalat, leading to its accession. These moves weakened the Khan’s position. Reports suggested the tribes might negotiate directly with Pakistan. Though the Khan protested, he ultimately accepted these accessions while holding firm on Makran. This sequence of events highlights the strategic maneuvering by both Pakistan and the local rulers to shape the region’s future.

Claims of military coercion are unfounded. While Pakistan moved forces to secure newly acceded territories, no orders for military action against Kalat exist. A faulty All-India Radio broadcast claiming Nehru’s refusal of Kalat’s accession caused panic, further pressuring the Khan. This episode underscores the role of misinformation and its potential to influence critical political decisions during this turbulent period.

On March 27, 1948, the Khan signed the instrument of accession, bringing Kalat under Pakistan’s control. The legality of the process remains undisputed by any foreign power or significant institution. While the Khan later criticized Pakistan’s neglect of Baluchistan post-Jinnah, he did not claim the accession was forced or illegal. Even nationalist leaders like Mir Ghous Bux Bizenjo avoided framing the accession as a violation. This legal and political consensus, however, did not translate into seamless integration, as Baluchistan’s challenges persisted.

Lessons and Challenges

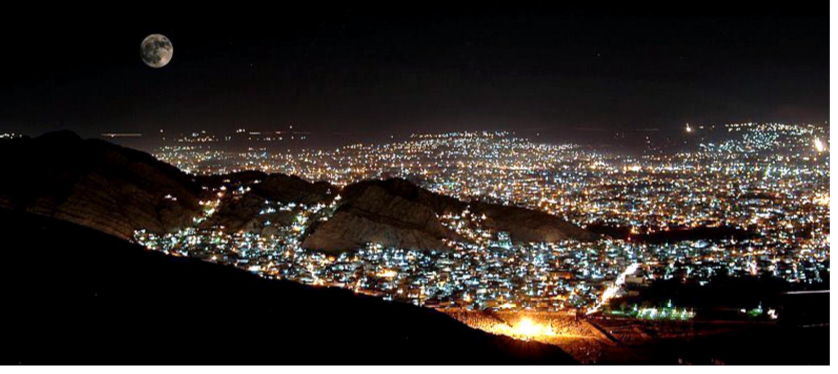

Pakistan’s coherent identity depends on reckoning with its history. Nationalism emerges from shared history, political involvement, and imagined brotherhood. In Baluchistan, knowledge and empathy can foster stability and unity. Addressing historical alienation is crucial to integrating this vast and beautiful region into Pakistan’s broader narrative. To achieve this, it is imperative to revisit the events of 1948 with a lens of understanding and to build bridges between the center and Baluchistan’s diverse communities.

Baluchistan’s history is not just a story of accession but also a testament to the resilience of its people and the intricate interplay of local, national, and international politics. By acknowledging this complexity, Pakistan can move toward a future where Baluchistan’s potential is fully realized, and its people feel an integral part of the Republic.