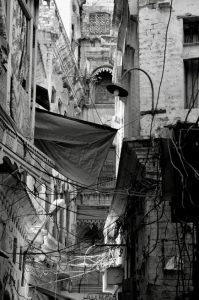

Zoom into a neighborhood in the old Rawalpindi districts. Think of old structures, cluttered and smushed together; paint peeling, bricks exposed, pipes jutting out, and narrow balconies overlooking tight streets with unpaved roads.

Think, within these old streets with water shortages and poor sewage infrastructure, a proud sport.

That sport?

Gun voyeurism and frequent violence. Constant death. A pride that stems from the competency of having the shiniest tools to kill the most efficiently. Now, within this neighborhood and its sport—the little children, all of whom witness it to some capacity; the helplessness of the mothers, sisters, and wives; the need to be more violent to survive.

Now zoom out, because you need to know why we’re looking into this image and why this story is important.

A degree, slowly growing in popularity and becoming the frequent talk in town: psychology. Is it bogus? A rationalization of some astrology-like fixation that has been blown out of proportion to leech families of money by introducing nonsense degrees? Or perhaps a natural science, slowly but surely warming its way through superstition in Pakistan?

A former clinical psychologist, for anonymity’s sake called Jane, and now an instructor in one of Pakistan’s best universities, commented on how the stigma of psychology is not the issue we need to be discussing, but rather the lack of regulation that can help this field achieve the impact it promises.

The matter at hand is that while developed countries seem to have the central bodies that regulate ethics, connections to emergency services that can help individuals pursuing psychological help if need be, and opportunity, Pakistan lacks the institutional integrity and systemic strength that is crucial to giving impactful psychological aid.

Zooming back into the crumbling neighborhood in Rawalpindi in the beginning, Jane shared how she encountered a little girl in an impossible situation. Fraught with mental disarray due to the violence she witnessed, her family turned to a ‘peer baba’ to help her sort the distress—even leaving her with this individual overnight. Imagine the horror of encountering this child, who was brought in by her mother for Jane to counsel. The mother emphasized that there was no way her family would allow her to come back to seek further counseling, that Jane had just one session with this distraught girl, and that there was no system in place to impact her positively in any way.

There is a lot that Pakistan needs to address before psychological help can even become efficient. The reality today is that most people who are able to seek psychological help have certain privileges to be able to access it. The most vulnerable people, who struggle with the disorders and trauma in a systematically helpless way, cannot be treated within their contexts. Like the little girl from this little neighborhood in Rawalpindi, who has nowhere to go and no way out. Or even the little girl’s mother, who sees her child suffering, who has likely seen why her child is suffering, and thus, to some capacity, is also eligible for psychological aid. What about the mother’s mother? The father? All those enmeshed in this life of horror?

To begin? Pakistan needs to start considering where it’s focusing its efforts and resources and who it’s neglecting. The potential of a society rests in its contentment and security of financial, physical, and emotional safety. The growth of psychology as a field is a step in the right direction, but the weight of the responsibility that comes with it has a helpless reality. Pakistan is in pressing need of reforms that sustain the practice of psychology for the people. As Jane puts it, every day she discusses with her colleague, who shares an office with her, why they have stopped practicing clinical psychology and how they need to pick it back up. They conclude by highlighting the helplessness of wanting to help someone that psychology alone will fail to solve.

Pakistan needs to facilitate the implementation of psychological aid by ensuring competency from practitioners and holding those without it accountable. Today, countless counseling and therapy providers do so without having proper credentials. Psychology students providing psychological first aid just after a bachelor’s with incomplete training is the norm. A norm that cannot be checked without a regulatory body and reform change.

It is high time the right conversations were had and the distracting ones put aside.