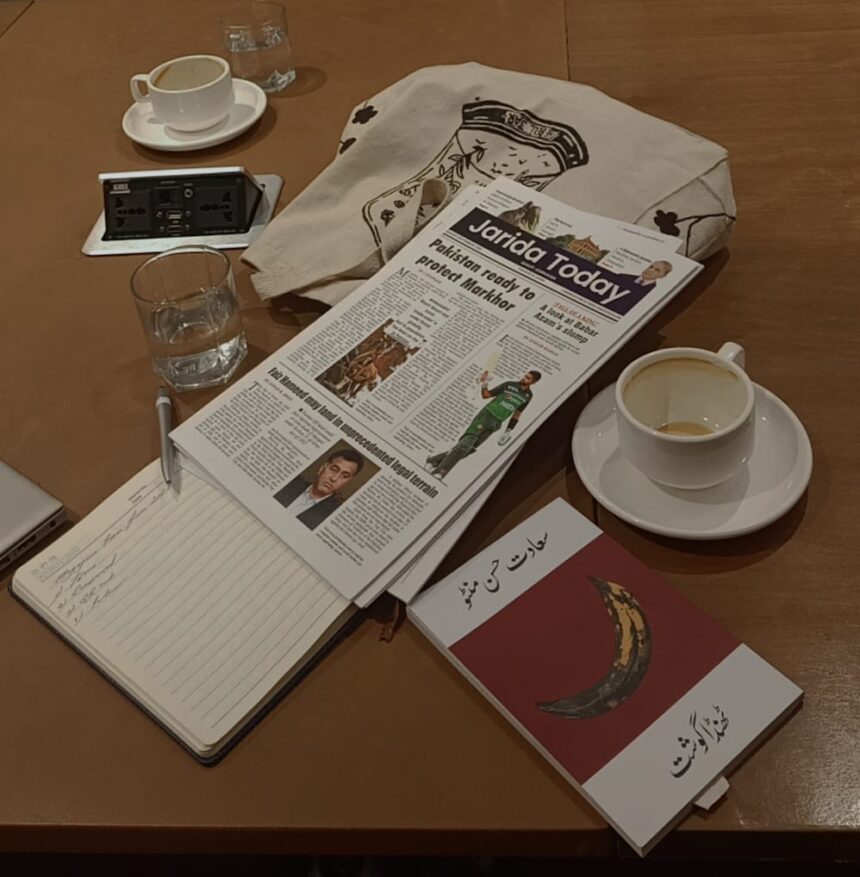

Magical thinking is the belief that you can will a reality into existence if you simply want it enough. In Pakistan, this is a belief most young people use to survive through the dulled-out days when resistance feels like a chore and being apolitical becomes the price you pay for peace of mind. In the year I started building Jarida, I thought I could rewrite the world, or at least edit it into coherence.

The first time I stepped in its office, I was scared I might have to pretend. Nice politics, conservative opinions, a safe wavelength to just float through another capitalistic venture disguised as indie revolt. It was a charming new space that seemed too eager to cater to what I—a self-proclaimed radical feminist and hater of all things systemic—had to say about the state of the country, particularly the way it diluted bold discourse. Being an angry young woman straight out of school is a scary way of living, and it is precisely this condition that Jarida so warmly welcomed.

My first task was to redesign the entirety of the magazine. As a perpetually detail-orientated person with an obsession with the nitty-gritties of the mundane, this was like an early birthday gift. And so began the process of rekindling the old flame of Jarida’s mission that we eventually ended up succinctly calling “beyond the narrative”.

From staying up late debating between the millions of shades that navy blue possessed to choosing between fonts—The Atlantic sleek or The New Yorker raw—and regularly redefining our nonexistent creative boundaries (that somehow always ended up politically challenging), we established a unique space for Jarida, carving into the bounds of Pakistani journalism one article at a time. But it did not stop there. We went from developing stylebooks that coincidentally went into administrative rabbit holes to arguing about the moral implications of subdued resistance towards the status quo we were so passionate to dismantle.

It is still a very controversial topic for most of the members at the office (the Creative Lead refuses to take solo responsibility for stimulating intellectual conversations), but we cherish it for the scope it provides for the radical, minority-run media collective we are blossoming in the heart of the city.

Jarida is no longer a magazine for me. It is beyond the conventional markers of a corporate media organisation existing in all its liberal grandiosity. Instead, it has birthed into a space for critical thought, both of and from the self. From brainstorming satire ideas that do justice to the abhorrent state of the world to inserting political euphemisms in abstract art, we are forging a bond built on the collective desire for change. As simple as it sounds, the youth of this country demand change, especially when it becomes offensive.

But Jarida is not the end for us. I hope to spend my twenties in a country that is flooded with more angry young women like me. Who see the lack of space catered to them, know that they are not welcome, and realise that they can create their own. While I do not have hopes for the state of Pakistani journalism in the foreseeable future, I can see Jarida paving the way for more independent collectives to push the boundaries of social and political critique in Pakistan. Gone are the days of relying upon your local news channel to tell you the truth. We saw that in the normalisation of undemocratic regime changes, the demonisation of populist figures otherwise loved on cameras, and the blatant complicity to become a mouthpiece for state-manufactured propaganda.

But we can look beyond the narrative we are spoon-fed on a daily basis. Our ability to evaluate sources, look past stooges, and compare Twitter discourses to reach a conclusion is dependent upon our commitment to combatting the apolitical epidemic. Pakistan needs people who relentlessly question, even when it is inconvenient. While I can see Jarida aiding this mission, I hope that ten years bring us more sister publications to collaborate on it.

My time at the magazine has been filled with fond memories, from intersectional analyses to conversations on the invisible lives of our pets. Some days are stressful and propel me to take drastic actions, like editing submissions for ten hours straight to scouting the best paper shops in Urdu Bazaar on an empty stomach and hoping the Editor in Chief does not faint before I do. I will miss the time I have spent here, more involved than I have ever been in anything before. My mind has embedded fragments of Gulberg into sections titled “soft politics” and coffee recommendations that satisfy my class consciousness.

In a way, this is a love letter to Jarida. It has evolved my perception of Lahore into a city of possibilities, especially for a woman in her twenties who hopes to change the world. So tomorrow, when I look back, I leave a place for more of me in Jarida and less of the despair that has otherwise captured this country’s people. I have faith in Jarida’s magical thinking.