Fellow writers, ever wonder how something as important as writing was ever invented? Well, unlike the discovery of fire, the wheel, and the internet, writing wasn’t technically discovered for what we use it for today; rather, it was invented in the modest act of counting jars of beer under the rule of the Mesopotamians.

Indeed, one of humankind’s most significant milestones of writing was not triggered by poetry or philosophy but by the practical and somewhat intoxicating needs of the Sumerians, who were also one of humanity’s earliest possible civilizations.

The Birthplace: Mesopotamia, the Cradle of Civilization

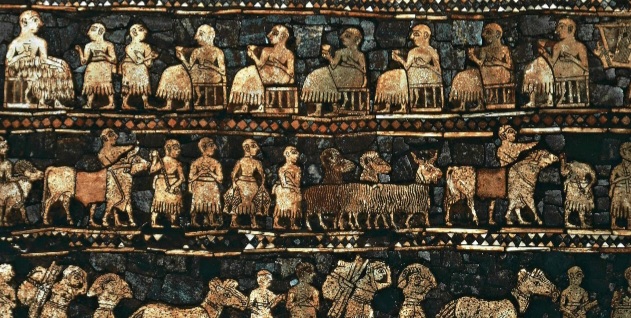

City-states such as Uruk, Lagash, and Eridu were founded by Sumerians around 3500 B.C.E. on the fertile lands between the Tigris and the Euphrates in present-day Iraq. These were the first cities with thousands of people relying on organized agriculture and trade and religious institutions.

The same happens with cities: when they grow, they grow more complex. People will need ways to keep track of everything: property, past harvests, goods, and oh yes, beer! Oral memory does not cut it anymore. Verbal agreements get forgotten, exaggerated, or denied. And when someone claimed they were only ‘borrowing’ ten jars of barley, people needed receipts to confirm the claim.

And this is how one of the greatest revolutions in history was born: writing.

Clay, Styluses, and the First “Receipts”

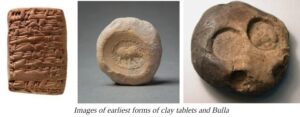

The first writing notions were of neither letters nor stories. They were imperfections made on clay tablets to record transactions of an economic nature.

These Sumerian scribes started with clay tokens—projections of goods like sheep or grains used to counter goods calculation, distribution, and taxation. Simply put, these tokens were placed in a clay envelope called a bulla, which was sealed to ensure no tampering would take place. The outside of the bulla was marked with those same symbols that the tokens inside were marked with. Eventually, it occurred to someone: why not just skip the tokens and draw the symbols directly onto a tablet?

This shortcut led to the development of pictographs—simple drawings representing objects. So, for instance, a jar of beer might be a drawing of a jug with foam on top, and the ‘drawing’ of a sheep might look, well, a little bit like an oddly shaped sheep, but it was all they needed to solve their economic problems. As the symbols became more abstract, scribes began pressing a stylus with a wedge-shaped end into soft clay in order to create a new system of writing called “cuneiform,” from the Latin for “wedge-shaped.” By about 3000 BCE, the Sumerians were completely into their writing system.

The Beer Factor: Why Alcohol Was So Important

And where does beer fit in?

Beer has historically held a primary rank in dietary choices for the Sumerian society. Beer is obtained from fermented barley. Hence, it was usually considered to be safer than drinking water, richer in nutrients, and frequently used as payment of wages to laborers, soldiers, and temple workers. At times workers were even paid in beer rations.

Many of the earliest tablets we have discovered are beer ledgers—the lists of ingredients and distributions and owe quantity to various people. For example, one of the best today, dated to about 3300 BCE, includes an image of a head eating food out of a bowl, followed by a conical vessel (a beer jar) along with some tally marks indicating quantities.

Simply put, it’s an ancient pay stub—”this person gets that much beer.”

Writing Evolves: From Math to Myths

It was beer that kindled the moguls of the early system: Sumerian writing developed more and more sophisticated by the time the third millennium BCE found cuneiform in use for everything from accounting to the recording of laws, literature, hymns, and history. Among the earliest of known literary works, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was written this way and preserved on clay tablets. Sumerians had developed writing to honor their deities, record royal proclamations, and pass tales to posterity.

Scribes trained in special schools known as edubbas. Becoming a scribe was an elite profession requiring years of study. These scribes could now write on nearly any topic: medicine, astronomy, religion, or bureaucratic records.

That is what beer-drawing began from: a couple of marks to an intricate scheme of around 600 signs and a writing tradition that would dominate whole empires.

Archaeological Discovery: Unearthing the Past

Cuneiform was only understood as valuable in the nineteenth century, when archaeologists started to excavate the ruins of Mesopotamia.

Thousands of clay tablets were uncovered in the city of Uruk (modern Warka) during the excavation campaign. Most of them contained undeciphered writing. But eventually, the work of several scholars-cum-archaeologists—and most notably Henry Rawlinson, who produced the greatest case of cuneiform by working on deciphering the Behistun Inscription (a multilingual relief carved in what is now modern Iran)—slowly began to part with its secrets.

As we know, Sumerians wrote practical records as well as mythology, poetry, elegies, and love songs. All of it tells that inside them, they had a rich life—not only loved and mourned but also believed in gods as well as paid taxes, and of course, people who were serious about their beers!

The Legacy of Sumerian Writing

The invention of writing announced the changing of the world. Laws could be written down, empires governed, and culture could be preserved. The Sumerians may have disappeared, but their writing legacy was passed on to the Babylonians and Assyrians, who also adapted cuneiform signs for their own languages.

Eventually, alphabet scripts would displace it. But the basic idea of somehow rendering thought into symbols on paper began in Sumer by an activity prompted to prove how many beers were owed to a temple worker.

Conclusion: From Bar Tabs to Civilization

Once writing came into play, it enabled human beings to recall memories, put forth their creativity, and develop complex societies—from measuring barley to composing epic tales. The next time you write a note or text, just remember: you are partaking in a 5,000-year-old space that was partially made possible by some clever Sumerians with a taste for beer.