It is apparent that the guarantee of citizens’ right to vote in 1991 remains one of the key obstacles to Bangladesh’s democracy. The functionality of democracy within the nation’s borders is fraught with a myriad of problems across every aspect. Different kinds of trust and responsibility with regard to voting are conveniently placed on the opposition. The people are highly divided, with large segments of society leaning towards violent behaviour—especially during elections. This type of political conflict is well known in modern Bangladesh.

Dominated by the Awami League and the BNP, Bangladesh has experienced a traditional two-party democratic political system. One striking feature of Bangladeshi democracy is the existence of this party system. Paradoxically, both the country and its people have lived under a one-party authoritarian regime that sought to eliminate all possible opposition to its centralised power. Unlike other modern communist nations, Bangladesh now lives under a government that outwardly demonstrates freedom while using its authority to strengthen its political foothold on the nation.

The people of Bangladesh have experienced heightened divisions for a long time, and these continue to deepen. The “politics of tribalisation” refers to the fragmentation of society into two distinct parts that are fundamentally at odds with each other and are subject to differentiating characteristics. The situation in Bangladesh appears to follow an ‘everyone against the other’ paradigm. It may be viewed as a kingdom with two “dynasties” residing within—one with ruling leaders, and the other perpetually opposing them. Neither of these two camps possesses any meaningful bargaining power with the other.

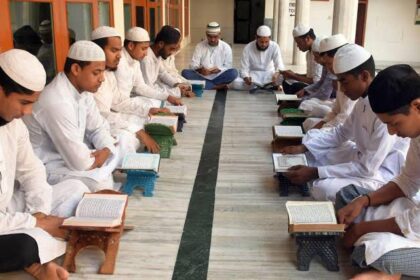

These segments of extreme polarisation manifest in various ways: “Bengali for Bangladeshi” nationalism; “Pro-Pakistan vs. Anti-Pakistan”; “Pro-Indian vs. Anti-Indian”; secularists vs. Islamists; or “Mujib vs. Zia”. These divides stem from the rivalry between leaders who unsuccessfully sought to become head of the independent state, and the intense, often improper use of power—especially by the heroes of the 1971 independence war. In this unstable environment, both the political and economic situations remain weak. The leaders are quickly made aware of the severity of the problem. Although certain features of a failed state remain, the fight to sustain them appears pointless and clearly doomed.

Political clientelism characterises the politics of Bangladesh. Other distinct features include the hereditary nature of its dynastic politics and the absence of internal democracy, both of which are outcomes and mechanisms of clientelistic politics. The existence of multiple patron-client relationships is evident between leaders and party loyalists. In fact, political parties in Bangladesh are multi-class systems integrating various patron-client structures in a multi-layered form. At the apex, the national party leaders seek local figures who can command sufficient loyalty among followers in their localities. These local leaders are granted middle-ranking positions—as local party officials, MPs for their constituencies, or both.

It has been observed that in the nomination of MPs, the decision of the party head is considered final. Moreover, the local leader secures votes primarily through personal networks and delivers them to the national party. The national party then supports its local representative, as long as it expects to gain power, by bestowing financial perks in the form of unilateral, unpaid constitutive benefits and funding for “political” expenditure in local electioneering—none of which is politically accountable public expenditure. These basic patronage-client fractions are widely popular across numerous villages, often controlled by mafias and bosses who operate through local factional networks known as Mastan and Mattabars.

Bangladesh’s political landscape is dominated by two major parties—the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Awami League—both currently led by figures who inherited power. For the past two decades, any attempt to challenge the dynastic rule of BNP Chairperson Khaleda Zia (widow of former President Ziaur Rahman) and Awami League President Sheikh Hasina (daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman) has been swiftly suppressed, often resulting in leadership change. This has stifled any real internal dissent and protected the entrenched ruling class within both parties from accountability to the public.

Many political analysts classify these parties as undemocratic in a constitutional sense due to their internal workings—debating, policymaking, and committee appointments revolve around personality cults. These dynamics confer personal patrimonial rights upon their leaders, whose control over the parties is absolute and legally enshrined in their constitutions. The BNP’s constitution, for instance, declares that the party chairman holds supreme authority and total responsibility over all executive functions. This includes the power to determine the roles, duties, and oversight of all organisational office-bearers at every level. Such consolidation of power significantly constrains internal dissent and the democratic processes of the party.

In Bangladesh, the clientelist, illiberal democratic, and electorally authoritarian bipolar party system presents a stark reality: controlling electoral violence is the overriding challenge the nation faces.